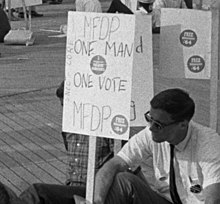

One man, one vote

This slogan is used by advocates of democracy and political equality, especially with regard to electoral reforms like universal suffrage, direct elections, and proportional representation.[5] During the mid-to-late 20th-century period of decolonisation and the struggles for national sovereignty, this phrase became widely used in developing countries where majority populations sought to gain political power in proportion to their numbers.[6][7][8] In the United States, the "one person, one vote" principle was invoked in a series of cases by the Warren Court in the 1960s during the height of related civil rights activities.Because of changes following industrialization and urbanization, most population growth had been in cities, and the bicameral state legislatures gave undue political power to rural counties.Successive Reform Acts by 1950 had both extended the franchise eventually to almost all adult citizens (barring convicts, lunatics and members of the House of Lords), and also reduced and finally eliminated plural voting for Westminster elections.Historians and political scholars have debated the extent to which the franchise for local government contributed to unionist electoral success in controlling councils in nationalist-majority areas.State legislatures, however, initially established election of congressional representatives from districts that were often based on traditional counties or parishes that had preceded founding of the new government.As a result, rural residents retained a wildly disproportionate amount of power in a time when other areas of the state became urbanized and industrialized, attracting greater populations.[20] Numerous court challenges were raised, including in Alabama, to correct the decades in which state legislative districts had not been redefined or reapportioned, resulting in lack of representation for many residents.However, in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) the United States Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren overturned the previous decision in Colegrove holding that malapportionment claims under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment were not exempt from judicial review under Article IV, Section 4, as the equal protection issue in this case was separate from any political questions.However, in the Western Australian and Queensland Legislative Assemblies, seats covering areas greater than 100,000 square kilometres (38,600 sq mi) may have fewer electors than the general tolerance would otherwise allow.[46][47] The following chart documents the years that the upper and lower houses of each Australian state parliament replaced malapportionment with the 'one vote, one value' principle.

direct electionprimary electionDemocratic National ConventionAtlantic City, New JerseyMississippi Freedom Democratic Partyslogandemocracypolitical equalityelectoral reformsuniversal suffragedirect electionsproportional representationLoosemore–Hanby indexGallagher indextrade unionistGeorge Howelldecolonisationdeveloping countriesanti-apartheidSouth AfricaWarren CourtEqual Protection ClauseU.S. Supreme CourtChief JusticeEarl WarrenReynolds v. SimsU.S. CongressWesberry v. SandersHouse of CommonsuniversitiesMembers of ParliamentPlural votingReform ActsconvictslunaticsHouse of LordsRepresentation of the People Act 1969Northern IrelandParliament of Northern IrelandunionistnationalistNorthern Ireland Civil Rights Association1969 Northern Ireland general electionUnited States Constitutiondecennial censusUnited States House of Representatives1920 censusReapportionment Act of 1929 State legislaturesdistrictsConstitutionGreat CompromiseFounding FathersArticle V of the United States ConstitutionActivismCivil Rights MovementCivil Rights Act of 1964Voting Rights Act of 1965African AmericansColegrove v. GreenBaker v. CarrFourteenth AmendmentGray v. Sanderscounty unit systemstate legislatureU.S. congressionalAvery v. Midland Countylocal governmentBoard of Estimate of City of New York v. MorrisEvenwel v. Abbottplurality votingranked votingFederal Constitutional Courtnegative voting weightTraining Wheels for CitizenshipCaliforniaminorsspecial-purpose districtsNative AmericantribesCherokeeChoctawnon-voting delegateHouse of RepresentativesAustraliaredistributionselectoral divisions of the House of RepresentativesSenateAustralian constitutionjoint sitting of ParliamentWhitlam Labor governmentCowperSolomonNorthern Territorymalapportionmentreferendum in 1974Section 128referendum proposalgerrymanderingJoh Bjelke-PetersenLiberal Party of AustraliaNational Party of AustraliaDemocracy IndexDemocratizationElectoral CollegeAnonymity (social choice)primariesleadership electionsDeclaration of IndependenceLincolnGettysburg AddressFifteenthSeventeenthNineteenth AmendmentsVortexLethal Weapon 2Halsey, Albert HenryPeter BrookeParliamentary Debates (Hansard)John H. WhyteConflict Archive on the InternetChristian Science MonitorParliamentary Library of Australia