Natacha Rambova

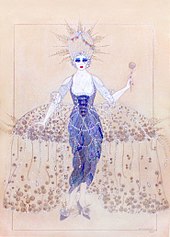

She was raised in San Francisco and educated in England before beginning her career as a dancer, performing under Russian ballet choreographer Theodore Kosloff in New York City.Rambova has been noted by fashion and art historians for her unique costume designs that drew on and synthesized a variety of influences, as well as her dedication to historical accuracy in crafting them.[2] Her father, Michael Shaughnessy, was an Irish Catholic from New York City who fought for the Union during the American Civil War and then worked in the mining industry.[10] During her childhood, Rambova spent summer vacations at the Villa Trianon in Le Chesnay, France with Edgar's sister, the French designer Elsie de Wolfe.[2] When Kosloff started work for fellow-Russian film producer Alla Nazimova at Metro Pictures Corporation (later MGM) in 1919, he sent Rambova to present some designs.Nazimova offered Rambova a position on her production staff as an art director and costume designer, proposing a wage of up to USD $5,000 per picture (equivalent to $76,047 in 2023).[27] The following year, she served as the art director on the DeMille production Forbidden Fruit (1921), in which she designed (with Mitchell Leisen) an elaborate costume for a Cinderella-inspired fantasy sequence.Although Valentino was still married to American film actress Jean Acker, he and Rambova moved in together within a year, having formed a relationship based more on friendship and shared interests than on emotional or professional rapport.While her association with Valentino lent Rambova a celebrity typically afforded to actors, their professional collaborations showed-up their differences more than their similarities, and she did not contribute to any of his successful films in spite of serving as his manager.[48] In the interval, they performed a promotional dance-tour for Mineralava Beauty Products, to keep his name in the spotlight, though when they reached her hometown of Salt Lake City, and she was billed as "The Little Pigtailed Shaughnessy Girl", Rambova was deeply insulted.[53][54] United Artists went so far as to offer Valentino an exclusive contract with the stipulation that Rambova had no negotiating power, and was disallowed from even visiting the sets of his films.[55] After the divorce proceedings began, Rambova moved on to other ventures: On March 2, 1926, she patented a doll she had designed with a "combined coverlet",[56][57] and also produced and starred in her own picture, Do Clothes Make the Woman?There, she immersed herself in several endeavors, appearing in vaudeville at the Palace Theatre[61] and writing a semi-fictional play entitled All that Glitters, which detailed her relationship with Valentino, and concluded in a fictionalized happy reconciliation.The following year, a second memoir was published entitled Rudolph Valentino Recollections (a variation of Rudy: An Intimate Portrait), in which she prefaces an addended final chapter by asking that only those "ready to accept the truth" read on; what follows is a detailed letter supposedly communicated by Valentino's spirit from an astral plane, which Rambova claimed to have received during an automatic writing session.[69] By late 1931, Rambova had grown uneasy about the economic situation of the United States during the Great Depression, and feared the country would experience a drastic revolution."[78] Rambova intended to use her research to generate a book, which she wanted Ananda Coomaraswamy to write, with the principal themes derived from astrology, theosophy, and Atlantis.[78] In an undated letter to Mary Mellon, she wrote: It is so necessary that gradually people be given the realization of a universal pattern of purpose and human growth, which the knowledge of the mysteries of initiation of the Atlantean past, as the source of our symbols of the Unconscious, gives ... Just as you said, knowledge of the meaning of the destruction of Atlantis and the present cycle of recurrence would give people an understanding of the present situation.[78]Rambova's intellectual investment in Egypt also led her to undertake work deciphering ancient scarabs and tomb inscriptions, which she began researching in 1946.[5] In the spring of 1950, the group was given permission to photograph and study inscriptions on golden shrines that had once enclosed the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun, after which they toured the Pyramid of Unas at Saqqara.[5] After completing the expedition in Egypt, Rambova returned to the United States, where, in 1954, she donated her extensive collection of Egyptian artifacts (accumulated over years of research) to the University of Utah's Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA).[80] She settled in New Milford, Connecticut, where she spent the following several years working as an editor on the first three volumes of Piankoff's series Egyptian Texts and Religious Representations,[76][81] which was based on the research he had done with Rambova and Thomas.[84] In 1957, Rambova moved to New Milford, Connecticut, and devoted her time to researching a comparative study of ancient religious symbolism, which she continued virtually unabated until her death.[88] With her health in rapid decline, Rambova's cousin, Ann Wollen, relocated her from her home in Connecticut to California, in order to help take care of her.[102] Whether Rambova was bisexual or homosexual is unclear; some have disputed such claims, including journalist David Wallace, who dismisses it as rumor in his 2002 book Lost Hollywood.[103] Biographer Morris also disputes the claim, writing in his epilogue of Madam Valentino that "the convenient ... allegation that Rambova was a lesbian collapses when one scrutinizes the facts.""[109] Rambova's sets incorporated shimmering shades of silver and white against sharp "moderne" lines, and blended elements of Bauhaus and Asian-inspired geometries."[107] Costume historian Deborah Landis named Rambova's white rubberized tunic (worn by Alla Nazimova) and the Art Deco-inspired imagery of Salome (1922) among the "most memorable in motion picture history.[115][116] Common preferences in her work included the dolman sleeve, long skirts with high waists, premium velvets, and intricate embroidery,[70] as well as incorporation of geometric shapes and use of "vivid colors ... that are violent and definite.[71] Rambova's scholarly work has been regarded as significant by contemporary academics in the fields of Egyptology and history: archaeologist Barbara Lesko notes that her contribution to Piankoff's Mythological Papyri "demonstrates her organizational skills and her commitment to searching out truths and does not reek of unfounded theories or other eccentricity.[120] Rambova has been depicted across several mediums, including visual art, film, and television: She was the subject of a 1925 painting by Serbian artist Paja Jovanović (donated by her mother to the UMFA in 1949).

Salt Lake City, UtahPasadena, CaliforniaCostumeRudolph ValentinoHeber C. KimballEgyptologythe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day SaintsTheodore KosloffspiritualismMellon GrantsPyramid of UnasThe Legend of ValentinoYvette MimieuxKen RussellValentinoMichelle PhillipsAlexandra DaddarioAmerican Civil WarCathedral of the MadeleineLe ChesnayElsie de WolfeRichard HudnutSurreyEnglandGreek mythologyAnna PavlovaSwan Lakeballerinastatutory rapeCecil B. DeMilleAlla NazimovaBillionsWhy Change Your Wife?Something to Think AboutForbidden FruitMitchell LeisenPaul PoiretLéon BakstAubrey BeardsleyThe Moving Picture WorldThe Woman God ForgotCamilleJean AckerbigamyCrown Point, Indianaspiritualistsautomatic writingThe Young RajahLatin loverFamous Players–LaskySaloméMonsieur BeaucaireUnited ArtistsWhat Price Beauty?Clive BrookWhen Love Grows ColdPicture PlayperitonitistelegramWoodlawn Cemeterythe BronxvaudevillePalace Theatreastral planeséancesEdward E. Paramore, Jr.PhotoplaycoutureBeulah BondiMae MurrayGreat DepressionJuan-les-PinsMallorcaMemphisThebesHoward CarterSpanish Civil Warheart attackBollingen Foundationpast lifeHelena BlavatskyGeorge GurdjieffastrologyHarper's BazaarAndrew W. Mellon FoundationAnanda CoomaraswamytheosophyAtlantisscarabsInstitut Français d'Archéologie OrientaleBook of CavernsCopticPistis SophiaVoice of the SilenceSutras of PatanjaliElizabeth ThomasTutankhamunSaqqaraUniversity of UtahMuseum of Fine ArtsNew Milford, ConnecticutWilliam C. HayesRichard ParkerpapyriYale UniversitysclerodermaLenox Hill HospitalArcadianursing homePasadenabisexualKenneth AngerHollywood Babylonconsummatedlavender marriageMarlene DietrichEva Le GallienneGreta GarboMercedes de AcostaDorothy NormanAnthony SlideArt DecoArt NouveaumoderneBauhausPat Kirkham