Magic lantern

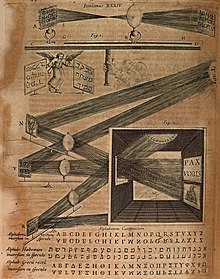

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name lanterna magica, was an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source.[9] The first photographic lantern slides, called hyalotypes, were invented by the German-born brothers Ernst Wilhelm (William) and Friedrich (Frederick) Langenheim in 1848 in Philadelphia and patented in 1850.[9][10][11] Apart from sunlight, the only light sources available at the time of invention in the 17th century were candles and oil lamps, which were very inefficient and produced very dim projected images.Giovanni Fontana, Leonardo da Vinci and Cornelis Drebbel described or drew image projectors that had similarities to the magic lantern.He knew Athanasius Kircher's 1645 edition of Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae[22] which described a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight.Christiaan's father Constantijn had been acquainted with Cornelis Drebbel who used some unidentified optical techniques to transform himself and to summon appearances in magical performances.[16] The oldest known document concerning the magic lantern is a page on which Christiaan Huygens made ten small sketches of a skeleton taking off its skull, above which he wrote "for representations by means of convex glasses with the lamp" (translated from French).[15] Walgensten is credited with coining the term Laterna Magica,[27] assuming he communicated this name to Claude Dechales who, in 1674, published about seeing the machine of the "erudite Dane" in 1665 in Lyon.[29] It has been suggested that this tradition is older and that instrument maker Johann Wiesel (1583–1662) from Augsburg may have been making magic lanterns earlier on and possibly inspired Griendel and even Huygens."[36] Kircher would eventually learn about the existence of the magic lantern via Thomas Walgensten and introduced it as "Lucerna Magica" in the widespread 1671 second edition of his book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae.In 1685–1686, Johannes Zahn was an early advocate for use of the device for educational purposes: detailed anatomical illustrations were difficult to draw on a chalkboard, but could easily be copied onto glass or mica.Carpenter also developed a "secret" copper plate printing/burning process to mass-produce glass lantern slides with printed outlines, which were then easily and quickly hand painted ready for sale.A common technique that is comparable to the effect of a panning camera makes use of a long slide that is simply pulled slowly through the lantern and usually shows a landscape, sometimes with several phases of a story within the continuous backdrop.This became a staple technique in phantasmagoria shows in the late 18th century, often with the lantern sliding on rails or riding on small wheels and hidden from the view of the audience behind the projection screen.[51]: 691 In 1645, Kircher had already suggested projecting live insects and shadow puppets from the surface of the mirror in his Steganographic system to perform dramatic scenes.[51]: 687 In 1668, Robert Hooke wrote about the effects of a type of magic lantern installation: "Spectators not well versed in optics, that should see the various apparitions and disappearances, the motions, changes and actions that may this way be represented, would readily believe them to be supernatural and miraculous.In 1675, German polymath and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz proposed a kind of world exhibition that would show all types of new inventions and spectacles.In a handwritten document he supposed it should open and close with magic lantern shows, including subjects "which can be dismembered, to represent quite extraordinary and grotesque movements, which men would not be capable of making" (translated from French).[55][56] Several reports of early magic lantern screenings possibly described moving pictures, but are not clear enough to conclude whether the viewers saw animated slides or motion depicted in still images.Lanternists could project the illusion of mild waves turning into a wild sea tossing the ships around by increasing the movement of the separate slides.An 1812 newspaper about a London performance indicates that De Philipsthal presented what was possibly a relatively early incarnation of a dissolving views show, describing it as "a series of landscapes (in imitation of moonlight), which insensibly change to various scenes producing a very magical effect.Possibly the first horizontal biunial lantern, dubbed the "Biscenascope" was made by the optician Mr. Clarke and presented at the Royal Adelaide Gallery in London on 5 December 1840.[78] It is thought that optical devices like concave mirrors and the camera obscura have been used since antiquity to fool spectators into believing they saw real gods and spirits,[78] but it was the magician "physicist" Phylidor who created what must have been the first true phantasmagoria show.He probably used mobile magic lanterns with the recently invented Argand lamp[86]: 144 to create his successful Schröpferischen, und Cagliostoischen Geister-Erscheinungen (Schröpfer-esque and Cagiostro-esque Ghost Apparitions)[87] in Vienna from 1790 to 1792.[78] When it opened in 1838, The Royal Polytechnic Institution in London became a very popular and influential venue with many kinds of magic lantern shows as an important part of its program.Popular magic lantern presentations included Henry Langdon Childe's dissolving views, his chromatrope, phantasmagoria, and mechanical slides.Possibly the phantasmagoria shows (popular in the west at that moment) inspired the rear projection technique, moving images and ghost stories.Japanese showmen developed lightweight wooden projectors (furo) that were handheld so that several performers could make the projections of different colourful figures move around the screen at the same time.It addresses the sustainable preservation of the massive, untapped heritage resource of the tens of thousands of lantern slides in the collections of libraries and museums across Europe.These include Pierre Albanese and glass harmonica player Thomas Bloch live Magic Lantern/Phantasmagoria shows since 2008 in Europe[95] and The American Magic-Lantern Theater.

Magic lantern (disambiguation)Carpenter and Westleyimage projectorphotographslensescamera obscuraslide projectorWillem 's GravesandeMuseum BoerhaaveChristiaan HuygensobjectiveStereopticonsdecalcomaniaPhiladelphiaArgand lamplimelightlumensarc lampprojectorGiovanni FontanaLeonardo da VinciCornelis DrebbeltelescopemicroscopeConstantijn HuygensGaspar SchottAthanasius KircherArs Magna Lucis et UmbraeAndré TacquetMartino MartiniLodewijkLouis XIV of FranceClaude DechalesGotlanduniversity of LeidenKing Frederick III of DenmarkJohann SturmCollegium ExperimentaleNürnbergAugsburgPierre PetitRichard ReeveBalthasar de MonconysSamuel PepysBacchusGottfried Wilhelm LeibnizAnne Claude de CaylusFrançois Dominique Séraphinshadow playHenry MoyesStéphanie Félicité, comtesse de GenlisMoses HoldenCarl Linnaeusmoviesslide projectorsphantasmagoriaanimateRobert HookeFrancesco EschinardiJohann Christoph WeigelZacharias Conrad von UffenbachPieter van MusschenbroekEdmé-Gilles Guyotjumping jacksChromatropeHenry Langdon ChildeMoiréCharles WheatstoneSpirographDissolving viewsdissolveDioramaPaul de PhilipsthalWitch of EndorAdelphi TheatregalvanometerphénakisticopeChoreutoscopeGreenwichKinetoscopeWilliam Friese-Greenenecromantic"physicist" PhylidorJohann Georg SchröpferCagliostroEtienne-Gaspard RobertKarakuri puppetsMuseum of PrecinemaRoyal Albert Memorial MuseumArmillaria meleaCantharellus cibariusChichorium intybusdrimeiaThomas BlochList of lantern slide collectionsProjector (disambiguation)ZoopraxiscopeCatadioptric telescopeHenry UnderhillTimby, KimDechales, Claude François MillietSutton, Charles WilliamDictionary of National BiographyCarpenter, PhilipGrau, OliverHarry Ransom CenterCleveland Public LibraryPrecursors of filmAlethoscopeAnorthoscopeChronophotographyCosmoramaElectrotachyscopeFlip bookKaiserpanoramaKinematoscopeMegalethoscopeMutoscopePeep showPhenakistiscopePraxinoscopeRaree showStereoscopeThaumatropeThéâtre OptiqueZoetrope