Seneca the Younger

Seneca had an immense influence on later generations—during the Renaissance he was "a sage admired and venerated as an oracle of moral, even of Christian edification; a master of literary style and a model [for] dramatic art.[7] His father was Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Elder, a Spanish-born Roman knight who had gained fame as a writer and teacher of rhetoric in Rome.[13] Seneca was taught the usual subjects of literature, grammar, and rhetoric, as part of the standard education of high-born Romans.[14] While still young he received philosophical training from Attalus the Stoic, and from Sotion and Papirius Fabianus, both of whom belonged to the short-lived School of the Sextii, which combined Stoicism with Pythagoreanism.[20] Cassius Dio relates a story that Caligula was so offended by Seneca's oratorical success in the Senate that he ordered him to commit suicide.[19] Seneca explains his own survival as due to his patience and his devotion to his friends: "I wanted to avoid the impression that all I could do for loyalty was die."[21] In AD 41, Claudius became emperor, and Seneca was accused by the new empress Messalina of adultery with Julia Livilla, sister to Caligula and Agrippina.[27] Seneca composed Nero's accession speeches in which he promised to restore proper legal procedure and authority to the Senate.[29] Cassius Dio even reports that the Boudica uprising in Britannia was caused by Seneca forcing large loans on the indigenous British aristocracy in the aftermath of Claudius's conquest of Britain, and then calling them in suddenly and aggressively.It was during these final few years that he composed two of his greatest works: Naturales quaestiones—an encyclopedia of the natural world; and his Letters to Lucilius—which document his philosophical thoughts.Cassius Dio, who wished to emphasize the relentlessness of Nero, focused on how Seneca had attended to his last-minute letters, and how his death was hastened by soldiers.After dictating his last words to a scribe, and with a circle of friends attending him in his home, he immersed himself in a warm bath, which he expected would speed blood flow and ease his pain.Alongside Seneca's apparent fortitude in the face of death, for example, one can also view his actions as rather histrionic and performative; and when Tacitus tells us that he left his family an imago suae vitae (Annales 15.62), "an image of his life", he is possibly being ambiguous: in Roman culture, the imago was a kind of mask that commemorated the great ancestors of noble families, but at the same time, it may also suggest duplicity, superficiality, and pretense.[38] As "a major philosophical figure of the Roman Imperial Period",[39] Seneca's lasting contribution to philosophy has been to the school of Stoicism.His writing is highly accessible[40][41] and was the subject of attention from the Renaissance onwards by writers such as Michel de Montaigne.[41] Stoicism was a popular philosophy in this period, and many upper-class Romans found in it a guiding ethical framework for political involvement.[43] It was once popular to regard Seneca as being very eclectic in his Stoicism,[49] but modern scholarship views him as a fairly orthodox Stoic, albeit a free-minded one.[63] Seneca's plays were widely read in medieval and Renaissance European universities and strongly influenced tragic drama in that time, such as Elizabethan England (William Shakespeare and other playwrights), France (Corneille and Racine), and the Netherlands (Joost van den Vondel).Fabulae crepidatae (tragedies with Greek subjects): Fabula praetexta (tragedy in Roman setting): Traditionally given in the following order: Seneca's writings were well known in the later Roman period, and Quintilian, writing thirty years after Seneca's death, remarked on the popularity of his works amongst the youth.[87] Various other antique and medieval texts purport to be by Seneca, e.g., De remediis fortuitorum, but with unconfirmed authorship, they have sometimes been referred-to as "Pseudo-Seneca".He appears not only in Dante, but also in Chaucer and to a large degree in Petrarch, who adopted his style in his own essays and who quotes him more than any other authority except Virgil.[92] His suicide has also been a popular subject in art, from Jacques-Louis David's 1773 painting The Death of Seneca to the 1951 film Quo Vadis.In his Apocolocyntosis he ridiculed the behaviors and policies of Claudius, and flattered Nero—such as proclaiming that Nero would live longer and be wiser than the legendary Nestor.[95] In this work Cardano portrayed Seneca as a crook of the worst kind, an empty rhetorician who was only thinking to grab money and power, after having poisoned the mind of the young emperor.Among the historians who have sought to reappraise Seneca is the scholar Anna Lydia Motto, who in 1966 argued that the negative image has been based almost entirely on Suillius's account, while many others who might have lauded him have been lost.Think of the barren image we should have of Socrates, had the works of Plato and Xenophon not come down to us and were we wholly dependent upon Aristophanes' description of this Athenian philosopher.

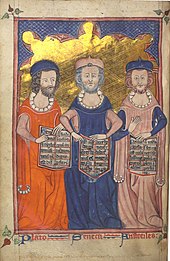

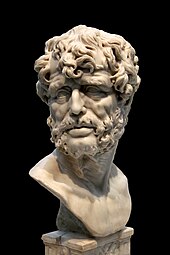

Double Herm of Socrates and SenecaCordubaHispania BaeticaRoman EmpireRoman ItalyEpistulae Morales ad LuciliumThyestesPhaedraSeneca the ElderHellenistic philosophyWestern philosophySchoolStoicismEthicsProblem of evilmononymouslyAncient RomedramatistsatiristLatin literatureColonia Patricia CordubaHispaniarhetoricphilosophyLucius Junius Gallio AnnaeanusCorsicaClaudiusSextus Afranius Burrusforced suicidePisonian conspiracyassassinatesuicidehis playstragedies124 lettersCórdobaBaeticaAnnaea gensLucius Annaeus Seneca the ElderRoman knightLucius Annaeus NovatusMiriam GriffinAttalusSotionPapirius FabianusSchool of the SextiiPythagoreanismvegetarianasthmatuberculosisGaius GaleriusPrefect of EgyptquaestorRoman SenateCassius DioCaligulaMessalinaJulia LivillaAgrippinaconsolationsPompeia PaulinaPolybiuspraetorshipEduardo BarrónMuseo del Pradopraetorian prefectsuffect consulApocolocyntosisOn ClemencyBritannicusTacitusPublius Suillius RufussestertiiNomentumBoudicaBritanniaconquest of BritainDe Vita BeataNaturales quaestionesLetters to LuciliusPeter Paul Rubensbleed to deathManuel Domínguez SánchezImperial PeriodMichel de MontaigneCleanthesChrysippusPosidoniusEpicurusLettersPlatonisteclecticSenecan tragedyTheatre of ancient RomeWoodcutFriedrich LeoHercules FurensAttic dramaEuripidesVirgilmedievalRenaissanceEuropeanuniversitiestragic dramaElizabethan EnglandWilliam ShakespeareCorneilleRacineJoost van den VondelThomas KydThe Spanish TragedyJacobean eraDana GioiaT. S. EliotsatireFabulae crepidataeHerculesTroadesPhoenissaeOedipusAgamemnonHercules OetaeusDaniël HeinsiusFabula praetextaOctavia