La Trinitaria (Dominican Republic)

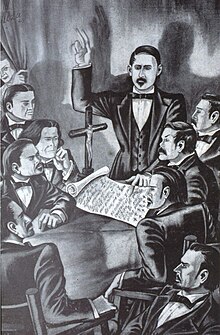

The founder, Juan Pablo Duarte, and a group of like minded young people, led the struggle to establish the Dominican Republic as a free, sovereign, and independent nation in the 19th century.[1] Acting in three-person cells and communicating through a complex system of passwords and codes, La Trinitaria focused on a three-pronged message of democracy, representative government, and independence for the Dominican Republic.At the age of 20, Duarte began the work of independence by sowing ideas of freedom among his friends, to whom he gave free education in his father's hardware store, located on Las Atarazanas Street.[2] While this was happening, a handwritten sheet called The Spanish Dominican, began to circulate through the city, with messages against the Haitian Government, established in the eastern part of the island in 1822 and directed by the leader Jean Pierre Boyer.That day and time was chosen because there would be a crowded procession, and Juan Pablo Duarte considered that it would be more convenient to keep the secret than holding the meeting in a remote place or in the early morning hours.[...] My friends, we are here to ratify the purpose that we had conceived of conspiring and making the people rise up against the Haitian power, in order to establish ourselves as a free and independent State with the name of the Dominican Republic.The Trinitaria is formed under its aegis, and each of its nine partners is obliged to reconstitute it, as long as one exists, until we fulfill the vow we make to redeem the homeland from the power of the Haitians.Serra, Ruiz and Ravelo validate their own attendance at that solemn meeting, as do those of Duarte, Pedro Alejandrino Pina and Juan Isidro Pérez.When Emiliano Tejera interrogated Duarte in Caracas, in 1864, he pointed out that Francisco del Rosario Sánchez and Matías Ramón Mella immediately entered La Trinitaria.For this reason they were disparagingly described as “Frenchified.” In addition to seeing it as impossible to confront Haitian military superiority, they considered that the presence of a foreign power was essential to promote economic progress, since the country was too poor.Many years later he wrote to his friend Félix María Delmonte his thoughts on the matter:[7] That fraction or rather that faction has been, is and will always be anything but Dominican; This is how it is seen in our history, representative of every anti-national party and therefore a born enemy of all our revolutions.Duarte maintained his intransigence against the conservative annexationists throughout his life.I recognize him as the possessor of two eminent virtues, the love of freedom and courage; […]His attitude was contrary to other Creole sectors that advocated returning to Spain, France, Great Britain, and the United States.During the aforementioned conversation, Duarte highlighted how pertinent it was to create an independent republic, not only free from the Haitians, but from all foreign power:[9] […] the Dominicans who on so many occasions have gloriously shed their blood, have they done so only to seal the affront that in reward for their sacrifices their dominators grant them the grace of kissing their hands?Long live the Dominican Republic!”A second aspect of Duarte's conceptions was his attachment to legality, since he sought to establish a regime based on the norms of institutions, and not on the accidental conveniences of individuals.Duarte sopposed these criteria and instilled in his disciples the principle of “race unity.” This meant the recognition that the Dominican nation had been structured through the mixture of diverse ethnic contributions, fundamentally that of Africans and Europeans, to give rise to a particular conglomerate of mulatto majority.The importance assigned to the issue had more than justified reasons, since the main obstacle facing the completion of the formation of the nation lay in the colonial criteria that established inequality between the ethnic-racial components.It is worth referring here to a reflection that the writer Washington de Peña makes on this matter when he suggests: "As it is, he is a corporal of the National Guard, who at the same time is General in Chief of the Army in the formation of a new republic."Another example of the founder's military courage - which journalist José Rafael Sosa relates - was when he returned to the country in March 1864, during the Dominican Restoration War, where Duarte shows his intention to join the battles that took place.they carried out, and ends by saying:[16] If I have returned to my country after so many years of absence, it has been to serve it with soul, life and heart, being that I have always been a reason for love among all true Dominicans, and never a stone of scandal, nor an apple of discord.By 1840, the Haitian government suspected a possible conspiracy in Santo Domingo, while La Trinitaria grew in followers.La Filantrópica, a society of apparent cultural nature, operated under the motto “Peace, union and friendship.” They held public meetings at Pedro Alejandro Pina's home, as literary evenings.However, the young people of Trinitaria did not waste time, and under Duarte, as well as by the Haitian anti-boyeristas Adolfo Nouel, and Artidor Gontieux, they headed that same afternoon to the fortress of the city with the purpose of taking it by force.A Popular Junta was installed in Santo Domingo and was in charge of exercising the function of provisional government, and included Duarte and other patriots who had fought alongside the Haitian liberals to overthrow Boyer.Duarte, aware of this, proceeded to take advantage of the situation that was presented to them to make contacts with other young people from the interior of the country in order to achieve independence for the eastern part of the island.The efforts carried out by Duarte were known by the Haitian liberals, who were not willing to give up the eastern part of the island, so they also began to maneuver with the help of other Dominican sectors in order to prevent the materialization of the ideals of the Trinitarios.Of these, the strongest after that of the Trinitario, was the one made up of mature men who had collaborated with the Haitians in various administrative positions and who sought to obtain help from France, in exchange for economic and political privileges.These circumstances can be related some aspects of the process of the pronouncements in favor of the cause of Independence, carried out with complete success in the towns of Cibao, which revealed that Duarte's ideal had been deeply and widely embraced throughout the region.[18] When the Provisional Government was installed on February 28, 1844, one of its first provisions consisted of appointing one of the Trinitarios, Pedro de Mena, as its Delegate to the people of Cibao, with the aim of informing them about the declaration of Independence, and achieving their adhesion to this cause.On March 4, at nightfall, when the Trinitarios of Santiago, called by Dr. Alejandro Llenas “The Separatists Club,” met at the house of Román Franco Bidó, a messenger sent from La Vega by Pedro arrived.Aware of the seriousness of the situation raised by the emissary of the Delegate of Mena, Morisset immediately gathered the main parents of the community in the Municipality and decided to entrust them with determining the side he should take.In this situation, General Morisset personally proceeded to lower the Haitian flag and “retired as a prisoner of war,” receiving him from Delegate Pedro de Mena who would later have him taken to Santo Domingo.Colonel José Gómez and General Francisco Salcedo were sent with forces to Los Hatos (of the Northwest), with the mission of planting the crossed flag on the border.In these observations, the rapid and well-coordinated movement of patriots, described in this story, was practically duplicated with equal success.

The TrinityJuan Pablo DuarteJuan Isidro PérezPedro Alejandro PinaJacinto de la ConchaRevolutionary movementDominican RepublicSpanishFrancisco del Rosario SánchezMatías Ramón Mellasecret societySanto DomingoHaitian occupation of Santo DomingoHoly TrinityGran ColombiaJean Pierre BoyerUnited StatesMariano Lebrón SaviñónBuenaventura BáezCharles de MontesquieuCharles Rivière-HérardBernard-Philippe-Alexis CarriéDominican Restoration WarEugenio de OchoaFrancisco Martínez de la RosaPort-au-PrinceSan CristóbalSantiagoFranceCharles-Rivière HérardJuan José DuarteAna ValverdeMaría Trinidad SánchezMaría Baltasara de los ReyesConcepción BonaOzama RiverSaint ThomasCarlos SoubletteVenezuelaTomás BobadillaPuerta del CondeCotuíJosé Desiderio ValverdeManuel JimenesSan Luis FortressJean-Louis PierrotBattle of SantiagoPedro SantanaAfro-DominicanAntonio DuvergéJosé Joaquín PuelloEusebio PuelloGabino PuelloManuel JiménesJuan Alejandro AcostaTrinityBlue PartyRed PartyDominican War of IndependenceSix Years' WarHistoryCacicazgoColonial governorsDevastations of OsorioSlave tradeEra de FranciaSpanish reconquestEspaña BobaSpanish HaitiUnification of HispaniolaWar of IndependenceSpanish occupation 1861–1865Restoration WarU.S. occupation 1916–1924RafaelHéctor TrujilloParsley massacreDominican Civil WarDOMREPCOVID-19 pandemicGeographyBorderCitiesCiudad ColonialHispaniolaIslandsMountainsMunicipalitiesProtected areasProvincesRiversPoliticsCabinetCongressSenateChamber of DeputiesConstitutionElectionsForeign relationsLGBTQ rightsenforcementMilitaryPolitical partiesPresidentEconomyPeso (currency)Central BankCompaniesEnergyTelecommunicationsTourismTransportDemographicsEducationLanguagePublic holidaysReligionWater and sanitationCultureAnthemCinemaCoat of armsCuisineLiteraturePeopleLGBTQ people