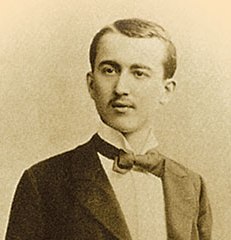

Ivan Đaja

[1][4][7][8] He has been described as the "restless researcher of the secret of life", who left a valuable creative and human mark in Serbian society, which was mostly pushed aside in the previous decades.His father Božidar “Boža” Đaja (1850, Dubrovnik-1914, Hinterbrühl) was a ship master, originally working as a sea captain, later switching to river transportation.[5][12] When Ivan was six, the family moved to Belgrade in 1890, where his father took over as the captain of a steamboat, Deligrad,[10][11] which was an official diplomatic ship of Serbian rulers.[8] In 1903 he enrolled at the Sorbonne, where one of his fellow students and best friends was Émile Herzog, later famous French author under the name Andre Maurois.He studied natural sciences (botany, physiology and biochemistry) under Albert Dastre, great scientific experimenter, himself a student of Claude Bernard.Đaja gave his final exam in 1905 and, mentored by Dastre, received a PhD on 23 July 1909 with the thesis in physiology Study on ferments of glycosides and carbohydrates in mollusks and crustaceans.[5] He also worked for a while at National Museum of Natural History with Paul van Tieghem, before spending five years at Marine station in Roscoff, Brittany.[5][8][14] Upon his return to Srbija, Đaja restored the Institute and became associate professor at the University's Faculty of Philosophy in 1919 obtaining the full professorship in 1921.[11] World War II interrupted his work again, as Đaja staunchly opposed the German-appointed puppet regime in Serbia.He helmed the process of collaboration between the two academies in an effort to realize his idea of creating a biology station for students located on the Adriatic Sea.[17] He was elected for his “seminal work on the behaviour of deep cooled warm blooded animals” and took over the academy seat which was left vacant after the death of Alexander Fleming.[8] After he founded the Institute, Đaja began his experimental work, adopting the motto Nulla dies sine experimentum (Not one day without the experiment).In the first phase, which started in his student days and lasted up to World War I, he concentrated on the research of the endogenic enzymes or ferments, which are produced by the glands of digestive organs.With his treatise State similar to the winter sleep of the hibernators achieved in rat by the means of barometric depression, published on 15 January 1940, he began researching the physiology of the deeply cooled homeothermous organisms.Apart from pure chemical processes in the human body, he was interested in philosophical decoding of the complex functional plexus in the natural world in general.His other initial studies were also centred on enzymology and published in magazines of the Parisian Biology society and French Academy of Sciences.When he died, he left several writings in manuscripts: Conversations in Dubrovnik, Short stories, Memories, Physiology and hypothermia and his autobiography Discovery of the world.[12] Ivan Đaja is one of the greatest Serbian physiologists and biologists who had the invaluable role in founding the experimentally based scientific physiology in Serbia.He founded the new scientific branch, high altitude hypothermia (or physiology of the cooled organisms) which has a growing application in modern medicine, much more than it had in Đaja's time.[3][8][14] Due to the intensive work of Đaja on establishing and keeping the professional links with foreign universities, he placed the Belgrade physiology school on a world map.After the war, when the Communists took over the government, he was introduced to the new authoritarian ruler Josip Broz Tito in 1945 as the "students mother and red rector".

Le HavreFranceBelgradeSerbiaYugoslaviaSorbonnehypothermiaMontyon PrizePhysiologyUniversity of BelgradeDoctoral advisorAlbert DastreSerbian CyrillicFrenchSerbianrectorSerbian Academy of Science and Artspopularizer of biologyadrenal glandsthermoregulationNormandyship-ownerDubrovnikHinterbrühlship masterDalmatiansailing shipsIlija M. Kolarac EndowmentFirst Belgrade GymnasiumÉmile ChartierAndre MauroisbotanybiochemistryClaude Bernardfinal examPolitikaNational Museum of Natural HistoryMarine stationRoscoffBrittanyYves DelagedocentFaculty of PhilosophyWorld War IViennaRed Cross of YugoslaviaInterbellumWorld War IIpuppet regime in SerbiaquislingBanjica concentration campSerbian Royal AcademyYugoslav Academy of Sciences and ArtsZagrebAdriatic SeaCroatiaFrench Academy of SciencesAlexander FlemingCaptain Miša's Mansionendogenicenzymesfermentsdigestive organsbioenergeticstreatisewinter sleephibernatorsbarometrichomeothermous organismsMilutin MilankovićBavaništePančevoSremska MitrovicaCanadaProfesorska KolonijaNikola PašićPeople's Radical PartyMinister of internal affairs of SerbiaCommittee of International Congresses of Military Medicine and PharmacyNatureIn memoriammonographopus magnumhypercapniapolymathSoutheast EuropehypercapnianAcadémie Nationale de Médecinedoctor honoris causaLegion of HonourNikola TeslaJovan CvijićVračarSerbian Order of the White Eagle, 4th classJosif PančićKopaonikJosip Broz TitoGeneral Encyclopedia of the Yugoslav Lexicographical Institute, III edition, Vol 2 C-FobJugoslavenski leksikografski zavod “Miroslav Krleža”Politikin ZabavnikStanoje StanojevićMatica SrpskaJovan HadžiAleksandar BelićVladimir Ćorović