Eurypterid

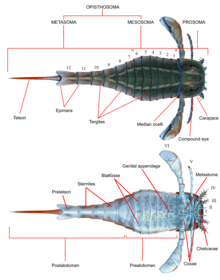

Only a handful of eurypterid groups spread beyond the confines of Euramerica and a few genera, such as Adelophthalmus and Pterygotus, achieved a cosmopolitan distribution with fossils being found worldwide.[1] The prosoma was covered by a carapace (sometimes called the "prosomal shield") on which both compound eyes and the ocelli (simple eye-like sensory organs) were located.This appendage, often preserved very prominently, has consistently been interpreted as part of the reproductive system and occurs in two recognized types, assumed to correspond to male and female.[9] Several different contributing factors to the large size of the pterygotids have been suggested, including courtship behaviour, predation and competition over environmental resources.An isolated 12.7 centimeters (5.0 in) long fossil metastoma of the carcinosomatoid eurypterid Carcinosoma punctatum indicates the animal would have reached a length of 2.2 meters (7.2 ft) in life, rivalling the pterygotids in size.Factors such as locomotion, energy costs in molting and respiration, as well as the actual physical properties of the exoskeleton, limit the size that arthropods can reach.It was attributed to the stylonurine eurypterid Hibbertopterus due to a matching size (the trackmaker was estimated to have been about 1.6 meters (5.2 ft) long) and inferred leg anatomy.These differently sized pairs would have moved in phase, and the short stride length indicates that Hibbertopterus crawled with an exceptionally slow speed, at least on land.The weight of its long abdomen would have been balanced by two heavy and specialized frontal appendages, and the center of gravity might have been adjustable by raising and positioning the tail.[22] Preserved fossilized eurypterid trackways tend to be large and heteropodous and often have an associated telson drag mark along the mid-line (as with the Scottish Hibbertopterus track).[25] Other eurypterid ichnogenera include Merostomichnites (though it is likely that many specimens actually represent trackways of crustaceans) and Arcuites (which preserves grooves made by the swimming appendages).Depending on the genus and species in question, other features such as size, the amount of ornamentation, and the proportional width of the body can be the result of sexual dimorphism.[50] There are also reports of even earlier fossil eurypterids in the Fezouata Biota of Late Tremadocian (Early Ordovician) age in Morocco, but these have yet to be thoroughly studied, [51] and are likely to be peytoiid appendages.[50] The Laurentian predators, classified in the family Megalograptidae (comprising the genera Echinognathus, Megalograptus and Pentecopterus), are likely to represent the first truly successful eurypterid group, experiencing a small radiation during the Late Ordovician.The extinction event, only known to affect marine life (particularly trilobites, brachiopods and reef-building organisms) effectively crippled the abundance and diversity previously seen within the eurypterids.Stylonurines, on the other hand, persisted through the period with more or less consistent diversity and abundance but were affected during the Late Devonian, when many of the older groups were replaced by new forms in the families Mycteroptidae and Hibbertopteridae.[67] However, various recent findings raise doubts about this, and suggest that these eurypterids were euryhaline forms that lived in marginal marine environments, such as estuaries, deltas, lagoons, and coastal ponds.[72] Adelophthalmus became the most common of all late Paleozoic eurypterids, existing in greater number and diversity than surviving stylonurines, and diversified in the absence of other eurypterines.[58] During the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian Adelophthalmus was widespread, living primarily in brackish and freshwater environments adjacent to coastal plains.[82] In 1843, Hermann Burmeister published his view on trilobite taxonomy and how the group related to other organisms, living and extinct, in the work Die Organisation der Trilobiten aus ihren lebenden Verwandten entwickelt.He considered the trilobites to be crustaceans, as previous authors had, and classified them together with what he assumed to be their closest relatives, Eurypterus and the genus Cytherina, within a clade he named "Palaeadae".[86] A fourth genus, Slimonia, based on fossil remains previously assigned to a new species of Pterygotus, was referred to the Eurypteridae in 1856 by David Page.[87] Jan Nieszkowski's De Euryptero Remipede (1858) featured an extensive description of Eurypterus fischeri (now seen as synonymous with another species of Eurypterus, E. tetragonophthalmus), which, along with the monograph On the Genus Pterygotus by Thomas Henry Huxley and John William Salter, and an exhaustive description of the various eurypterids of New York in Volume 3 of the Palaeontology of New York (1859) by James Hall, contributed massively to the understanding of eurypterid diversity and biology.[90] In 1912, John Mason Clarke and Rudolf Ruedemann published The Eurypterida of New York in which all eurypterid species thus far recovered from fossil deposits there were discussed.[91] In line with earlier authors, Clarke and Ruedemann also supported a close relationship between the eurypterids and the horseshoe crabs (united under the class Merostomata) but also discussed alternative hypotheses such as a closer relation to arachnids.[94] Due to these similarities, the xiphosurans and eurypterids have often been united under a single class or subclass called Merostomata (erected to house both groups by Henry Woodward in 1866).Though xiphosurans (like the eurypterids) were historically seen as crustaceans due to their respiratory system and their aquatic lifestyle, this hypothesis was discredited after numerous similarities were discovered between the horseshoe crabs and the arachnids.[99] Eurypterids were recovered as closely related to arachnids instead of xiphosurans, forming the group Sclerophorata within the clade Dekatriata (composed of sclerophorates and chasmataspidids).Lamsdell noted that it is possible that Dekatriata is synonymous with Sclerophorata as the reproductive system, the primary defining feature of sclerophorates, has not been thoroughly studied in chasmataspidids.[110] Rhenopteridae Parastylonuridae Stylonuridae Hardieopteridae Kokomopteridae Drepanopteridae Hibbertopteridae Mycteroptidae Moselopteridae Onychopterellidae Dolichopteridae Eurypteridae Strobilopteridae Megalograptidae Carcinosomatidae Mixopteridae Waeringopteridae Adelophthalmidae Hughmilleriidae Pterygotidae Slimonidae

EurypterusEurypteridaeDarriwilianLate PermianPreꞒJiangshanianEurypterus remipesState Museum of Natural History KarlsruheKarlsruheGermanyScientific classificationEukaryotaAnimaliaArthropodaChelicerataSclerophorataBurmeisterEurypterinaStylonurinaDienerDorfopterusMarsupipterusSynonymsHaeckelStørmerarthropodsOrdovicianmillion years agoEarly OrdovicianLate CambrianPaleozoicchelicerateSilurianDevonianLate Devonian extinction eventPermian–Triassic extinction eventmarinebrackishfresh waterscorpionsrespiratory systemAncient GreekJaekelopterusAlkenopterusNorth AmericaEuropeEuramericaAdelophthalmusPterygotuscosmopolitan distributionsegmentedcuticleproteinschitincheliceratestagmataprosomaopisthosomacarapacecompound eyesocellicheliceraehomologousPterygotidaechelaesubordertelsonPterygotioideaHibbertopteridaeMycteroptidaeCarcinosomatoideaEusarcanamesosomametasomaventralhorseshoe crabsunderwater respirationanteriorPterygotus grandidentatusPentecopterus decorahensisAcutiramus macrophthalmusCarcinosoma punctatumJaekelopterus rhenaniaetaxonomic affinityAlkenopterus burglahrensisEmsianKlerf FormationErettopterus grandisHibbertopterus wittebergensisAcutiramusmoltingexoskeletonArthropleuraeurypterineHibbertopterusstylonurinesea floorfossil trackwayParastylonurusEurypteroideawater beetlessubaqueous flightsea turtlessea lionsdrag coefficientholotypePalmichnium kosinkiorumMixopteruscenter of gravitySouth AfricaGondwanaPalmichniumMerostomichnitesArcuitesposteriorisopodsOniscusspinulesinvaginationsplastrontracheaepleopodsasphyxiationLarvalinstarsStrobilopterus