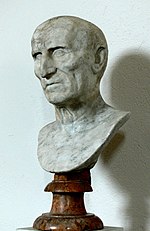

The Twelve Caesars

The subjects consist of: Julius Caesar (d. 44 BC), Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, Titus, Domitian (d. 96 AD).[citation needed] The book still provides valuable information on the heritage, personal habits, physical appearance, lives, and political careers of the first Roman emperors mentioning key details which other sources omit.For example, Suetonius is the main source on the lives of Caligula, his uncle Claudius, and the heritage of Vespasian (the relevant sections of the Annals by his contemporary Tacitus having been lost).Suetonius then narrates that period describing Caesar's disengagement with a wealthy girl called Cossutia, engagement with Cornelia during the civic strife.Amused at the lowness of the initial ransom they sought to ask for him, Caesar insisted that they raise his price to 50 talents, and promised that one day he would find them and crucify them (this was the standard punishment for piracy during this time).Suetonius mentions Caesar's famous crossing of the Rubicon (the border between Italy and Cisalpine Gaul), on his way to Rome to start a Civil War against Pompey and ultimately seize power.Suetonius quotes the Roman dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla as saying, "Beware the boy with the loose clothes, for one day he will mean the ruin of the Republic."Before he died, Julius Caesar had designated his great-nephew, Gaius Octavius (who would be named Augustus by the Roman Senate after becoming emperor), as his adopted son and heir.His declaration of the end of the Civil Wars that had started under Julius Caesar marked the historic beginning of the Roman Empire, and the Pax Romana.It has also been noted by several sources that the entire work of The Twelve Caesars delves more deeply into personal details and gossip relative to other contemporary Roman histories.Suetonius opens his book on Tiberius by highlighting his ancestry as a member of the patrician Claudii, and recounts his birth father's career as a military officer both under Caesar and as a supporter of Lucius Antonius in his rebellion against Octavian.After briefly mentioning military and administrative successes, Suetonius tells of perversion, brutality and vice and goes into depth to describe depravities he attributes to Tiberius.Despite the lurid tales, modern history looks upon Tiberius as a successful and competent emperor[citation needed] who at his death left the state treasury much richer than when his reign began.He reports that Caligula married his sister to Lepidus (though Caligula still treated her like a wife), threatened to make his horse consul, and that he sent an army to the northern coast of Gaul and as they prepared to invade Britain, one rumour had it that he had them pick seashells on the shore (evidence shows that this could be a fabrication as the word for shell in Latin doubles as the word that the legionaries of the time used to call the 'huts' that the soldiers erected during the night while on campaign).Caligula was an avid fan of gladiatorial combats; he was assassinated shortly after leaving a show by a disgruntled Praetorian Guard captain, as well as several senators.Nonetheless, Claudius suffered from a variety of maladies, including fits and epileptic seizures, a funny limp, as well as several personal habits like a bad stutter and excessive drooling when overexcited.In his account of Caligula, Suetonius also includes several letters written by Augustus to his wife, Livia, expressing concern for the imperial family's reputation should Claudius be seen with them in public.Per Suetonius, Claudius, under suggestions from his wife Messalina, tried to shift this deadly fate from himself to others by various fictions, resulting in the execution of several Roman citizens, including some senators and aristocrats.Claudius' dining habits figure in the biography, notably his immoderate love of food and drink, and his affection for the city taverns.His reign came to an end when he was murdered by eating from a dish of poisoned mushrooms, probably supplied by his last wife Agrippina in an attempt to have her own son from a previous marriage, the future emperor Nero, ascend the throne.These concerts would last for hours on end, and some women were rumored to give birth during them, or men faking death to escape (Nero forbade anyone from leaving the performance until it was completed).Suetonius quotes one Roman who lived around this time who remarked that the world would have been better off if Nero's father Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus had married someone more like the castrated boy.Suetonius recounts how Nero, while watching Rome burn, exclaimed how beautiful it was, and sang an epic poem about the sack of Troy while playing the lyre.Suetonius begins by describing the humble antecedents of the founder of the Flavian dynasty and follows with a brief summary of his military and political career under Aulus Plautius, Claudius and Nero and his suppression of the uprising in Judaea.Suetonius presents Vespasian's early imperial actions, the reimposition of discipline on Rome and her provinces and the rebuilding and repair of Roman infrastructure damaged in the civil war, in a favourable light, describing him as 'modest and lenient' and drawing clear parallels with Augustus.At the time of his death, he "[drew] back the curtains, gazed up at the sky, and complained bitterly that life was being undeservedly taken from him – since only a single sin lay on his conscience."The war ended in 88 in a compromise peace which left Decebalus as king and gave him Roman "foreign aid" in return for his promise to help defend the frontier.Those closest to him suffered the most, and after a reign of terror at the imperial court Domitian was murdered in 96 AD; the group that killed him, according to Suetonius, included his wife, Domitia Longina, and possibly his successor, Nerva.The oldest surviving copy of The Twelve Caesars was made in Tours in the late 8th or early 9th century AD, and is currently held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.John Lydus, in his 6th-century book De magistratibus populi Romani, quotes the dedication (from the now-lost prologue) to Septicius Clarus, then prefect of the Praetorian cohort.

Caesars (band)SuetoniusBiographyRoman EmpireJulius CaesaremperorsGaius Suetonius TranquillusAugustusTiberiusCaligulaClaudiusVitelliusVespasianDomitianHadrianPraetorian prefectGaius Septicius ClarusPrincipateRepublicTacitusprincepsAnnalsChrestusChristHistoricity of JesusCivil WarPompey the GreatVeni, vidi, vicipirates in the Mediterranean SeatalentscrucifyquaestorHispaniaAlexander the Greatcrossing of the RubiconCisalpine GaulRoman calendarParthian EmpirePompeyResidenz, MunichRoman dictatorLucius Cornelius SullaSocial WarmonarchyBrutuskai su, teknonet tu, BruteShakespeareGlyptothekMunichGaius OctaviusRoman SenateadoptedJulia MinorlegionsMark AntonyBattle of ActiumimperatorPax RomanaPandateriaconsulshipCiceroRoman governorHispania UlteriorBattle of Teutoburg ForestLegio XVIILegio XVIIILegio XIXArminiusQuinctilius VarusDanubeborder of the empireClaudiiLucius AntoniusVipsania AgrippinaRhodesPostumus AgrippaGemonian stairsTiber RivercaligaGermanicuspietasJupiterides of MarchflamingoPraetorian GuardCassius Dioepileptic seizuresfreedmenMessalinaAgrippinaBritannicusSporuscastratedGnaeus Domitius AhenobarbusRome burnedYear of the Four EmperorspatricianMarcus Salvius OthoBattle of BedriacumJudaeaFlavian dynastyAulus PlautiusPecunia non oletsiege of JerusalemHerod's TempleJewish diasporaBereniceFlavian AmphitheaterMount Vesuviusdeifiedautocratequestrian classpublic moralitylower DanubeDaciansRomaniaDecebalusAntonius SaturninusDomitia LonginaFive Good EmperorsBibliothèque nationale de FranceJohn LydusMarius MaximusHistoria AugustaEinhard