Rebellion

In many of these cases, the opposition movement saw itself not only as nonviolent but also as upholding their country's constitutional system against a government that was unlawful, for example if it had refused to acknowledge its defeat in an election.Rebellion is studied, in Theda Skocpol's words, by analyzing "objective relationships and conflicts among variously situated groups and nations, rather than the interests, outlooks, or ideologies of particular actors in revolutions".The central tenet of Marxist philosophy, as expressed in Das Kapital, is the analysis of society's mode of production (societal organization of technology and labor) and the relationships between people and their material conditions."Collective violence", Tilly writes, "is the product of just normal processes of competition among groups in order to obtain the power and implicitly to fulfill their desires".[19] He proposes two models to analyze political violence: Revolutions are included in this theory, although they remain for Tilly particularly extreme since the challenger(s) aim for nothing less than full control over power.[22] The success of a revolutionary movement hinges on "the formation of coalitions between members of the polity and the contenders advancing exclusive alternative claims to control over Government.".While the latter aims to change the polity, the former is "rapid, basic transformations of a society's state and class structures; and they are accompanied and in part carried through by class-based revolts from below".Skocpol identifies three stages of the revolution in these cases (which she believes can be extrapolated and generalized), each accordingly accompanied by specific structural factors which in turn influence the social results of the political action: Here is a summary of the causes and consequences of social revolutions in these three countries according to Skocpol:[33] The following theories are all based on Mancur Olson's work in The Logic of Collective Action, a 1965 book that conceptualizes the inherent problem with an activity that has concentrated costs and diffuse benefits.In fact, he argues the "free rider" possibility, a term that means to reap the benefits without paying the price, will deter rational individuals from collective action.This formalist view of the collective action problem stresses the importance of individual economic rationality and self-interest: a peasant, according to Popkin, will disregard the ideological dimension of a social movement and focus instead on whether or not it will bring any practical benefit to him.Popkin argues that peasants rely on their "private, family investment for their long run security and that they will be interested in short term gain vis-à-vis the village.[37] Popkin stresses this "investor logic" that one may not expect in agrarian societies, usually seen as pre-capitalist communities where traditional social and power structures prevent the accumulation of capital.[38] Political Scientist Christopher Blattman and World Bank economist Laura Ralston identify rebellious activity as an "occupational choice".Economist Eli Berman and Political Scientist David D. Laitin's study of radical religious groups show that the appeal of club goods can help explain individual membership.Contrary to established beliefs, they also find that a multiplicity of ethnic communities make society safer, since individuals will be automatically more cautious, at the opposite of the grievance model predictions.This perspective still adheres to Olson's framework, but it considers different variables to enter the cost/benefit analysis: the individual is still believed to be rational, albeit not on material but moral grounds.Thompson goes on to write that "[the riots were] legitimized by the assumptions of an older moral economy, which taught the immorality of any unfair method of forcing up the price of provisions by profiteering upon the necessities of the people".In 1991, twenty years after his original publication, Thompson said that his, "object of analysis was the mentalité, or, as [he] would prefer, the political culture, the expectations, traditions, and indeed, superstitions of the working population most frequently involved in actions in the market."[48] The opposition between a traditional, paternalist, and the communitarian set of values clashing with the inverse liberal, capitalist, and market-derived ethics is central to explain rebellion.The "convergence of local motives and supralocal imperatives" make studying and theorizing rebellion a very complex affair, at the intersection between the political and the private, the collective and the individual.[58] Rebellions thus cannot be analyzed in molar categories, nor should we assume that individuals are automatically in line with the rest of the actors simply by virtue of ideological, religious, ethnic, or class cleavage.

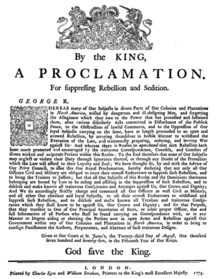

Rebellion (disambiguation)Revolt (disambiguation)Insurrection (disambiguation)Uprising (disambiguation)InsurgencyPolitical revolutionBourgeoisCommunistCounter-revolutionaryDemocraticProletarianColourFrom aboveNonviolentPassivePermanentSocialBoycottCivil disorderCivil warClass conflictContentious politicsCoup d'étatDemonstrationHuman chainDirect actionGuerrilla warfareMass mobilizationMutinyProtestResistanceDisobedienceSamizdatStrike actionTax resistanceTerrorEnglishAtlanticAmericanBrabantLiègeFrenchHaitianSpanish AmericanSerbianBelgianItalian statesFebruaryGermanHungarianEurekaBulgarian unificationPhilippineSecondYoung TurkMexicanXinhaiCultural1917–1923RussianSiameseSpanishAugustGuatemalanHungarian (1956)RwandanNicaraguanArgentineCarnationPeople PowerYogurtVelvetRomanianSingingBolivarianBulldozerOrangeKyrgyzArab SpringTunisianEgyptianYemeniEuromaidanSecond Arab SpringSudaneseLockian philosophyresponsibility of the people to overthrow unjust governmentList of revolutions and rebellionsstorming of the BastilleFrench RevolutionGreek War of IndependenceOttoman EmpireGreecebelligerentsCivil resistanceGeorge IIIProclamation of RebellionTheda SkocpolKarl Marxpolitical violenceDas KapitalTed Gurrpolitical regimerelative deprivationCharles Tillyprofit maximizationMancur OlsonThe Logic of Collective Actionproblempublic goodcollective actionfree ridersmallholderopportunity costclub goodspublic goodsEli BermansuicideGreed versus grievancePaul CollierGrievanceethniceconomic inequalitydiasporaThe Moral Economy of the PeasantJames C. Scott