Brown v. Board of Education

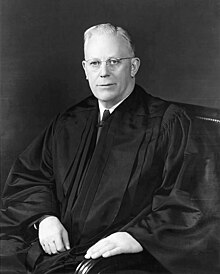

The Browns and twelve other local black families in similar situations filed a class-action lawsuit in U.S. federal court against the Topeka Board of Education, alleging its segregation policy was unconstitutional.The Court ruled that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal," and therefore laws that impose them violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.In the Southern United States, the reaction to Brown among most white people was "noisy and stubborn", especially in the Deep South where racial segregation was deeply entrenched in society.[5] Many Southern governmental and political leaders embraced a plan known as "massive resistance", created by Senator Harry F. Byrd, in order to frustrate attempts to force them to de-segregate their school systems.Beginning in the 1930s, a legal strategy was pursued, led by scholars at Howard University and activists at the NAACP, that sought to undermine states' public education segregation by first focusing on the graduate school setting.[7] This led to success in the cases of Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950), suggesting that racial segregation was inherently unequal (at least in some settings), which paved the way for Brown.The United States and the Soviet Union were both at the height of the Cold War during this time, and U.S. officials, including Supreme Court justices, were highly aware of the harm that segregation and racism were doing to America's international image.Chief Justice Earl Warren, nominated to the Supreme Court by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, echoed Douglas's concerns in a 1954 speech to the American Bar Association, proclaiming that "Our American system like all others is on trial both at home and abroad, ... the extent to which we maintain the spirit of our constitution with its Bill of Rights, will in the long run do more to make it both secure and the object of adulation than the number of hydrogen bombs we stockpile.Notable among the Topeka NAACP leaders were the chairman McKinley Burnett; Charles Scott, one of three serving as legal counsel for the chapter; and Lucinda Todd.The named African-American plaintiff, Oliver Brown, was a parent, a welder in the shops of the Santa Fe Railroad, as well as an assistant pastor at his local church.[20] Judge Walter Huxman wrote the opinion for the three-judge District Court panel, including nine "findings of fact," based on the evidence presented at trial."[28] British barrister and parliamentarian Anthony Lester has written that "Although the Court's opinion in Brown made no reference to these considerations of foreign policy, there is no doubt that they significantly influenced the decision.Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.The Court did not close with an order to implement the integration of the schools of the various jurisdictions.However, the Deep South made no moves to obey the judicial command, and in some districts there can be no doubt that the Desegregation decision hardened resistance to integration proposals.President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded by asserting federal control over the Arkansas National Guard and deploying troops from the U.S. Army's 101st Airborne Division stationed at Fort Campbell to ensure the black students could safely register for and attend classes.But Florida Governor LeRoy Collins, though joining in the protest against the court decision, refused to sign it, arguing that the attempt to overturn the ruling must be done by legal methods.[53] When Medgar Evers sued in 1963 to desegregate schools in Jackson, Mississippi, White Citizens Council member Byron De La Beckwith murdered him.However, in 1956, a special session of the Virginia legislature adopted a legislative package which allowed the governor to simply close all schools under desegregation orders from federal courts.The intellectual roots of Plessy v. Ferguson, the landmark United States Supreme Court decision upholding the constitutionality of racial segregation in 1896 under the doctrine of "separate but equal" were, in part, tied to the scientific racism of the era.[76][77] William Rehnquist wrote a memo titled "A Random Thought on the Segregation Cases" when he was a law clerk for Justice Robert H. Jackson in 1952, during early deliberations that led to the Brown v. Board of Education decision.[80] Later, at his 1986 hearings for the slot of Chief Justice, Rehnquist put further distance between himself and the 1952 memo: "The bald statement that Plessy was right and should be reaffirmed, was not an accurate reflection of my own views at the time.[82][83] Chief Justice Warren's reasoning was broadly criticized by contemporary legal academics with Judge Learned Hand decrying that the Supreme Court had "assumed the role of a third legislative chamber"[84] and Herbert Wechsler finding Brown impossible to justify based on neutral principles.Indeed, Brown I itself did not need to rely upon any psychological or social-science research in order to announce the simple, yet fundamental truth that the Government cannot discriminate among its citizens on the basis of race.[86]Some Constitutional originalists, notably Raoul Berger in his influential 1977 book "Government by Judiciary," make the case that Brown cannot be defended by reference to the original understanding of the 14th Amendment.[89] The case also has attracted some criticism from more liberal authors, including some who say that Chief Justice Warren's reliance on psychological criteria to find a harm against segregated blacks was unnecessary.For example, Drew S. Days III has written:[90] "we have developed criteria for evaluating the constitutionality of racial classifications that do not depend upon findings of psychic harm or social science evidence.They are based rather on the principle that 'distinctions between citizens solely because of their ancestry are by their very nature odious to a free people whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equality,' Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943). . . ."The purpose that brought the fourteenth amendment into being was equality before the law, and equality, not separation, was written into the law.In June 1987, Philip Elman, a civil rights attorney who served as an associate in the Solicitor General's office during Harry Truman's term, claimed he and Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter were mostly responsible for the Supreme Court's decision, and stated that the NAACP's arguments did not present strong evidence.[91] Elman has been criticized for offering a self-aggrandizing history of the case, omitting important facts, and denigrating the work of civil rights attorneys who had laid the groundwork for the decision over many decades.When faced with a court order to finally begin desegregation in 1959 the county board of supervisors stopped appropriating money for public schools, which remained closed for five years, from 1959 to 1964.

Supreme Court of the United StatesOliver BrownL. Ed.U.S. LEXISA.L.R.2dF. Supp.D. Kan.F.R.D.10th Cir.F. Supp. 2dpublic schoolsEqual Protection ClauseFourteenth AmendmentDistrict Court of KansasEarl WarrenHugo BlackStanley F. ReedFelix FrankfurterWilliam O. DouglasRobert H. JacksonHarold H. BurtonTom C. ClarkSherman MintonU.S. Const. amend. XIVPlessy v. FergusonCumming v. Richmond County Board of EducationBerea College v. KentuckylandmarkU.S. Supreme CourtU.S. stateracial segregationU.S. Constitutionseparate but equalintegrationcivil rights movementimpact litigationTopeka, Kansasclass-actionU.S. District Court for the District of KansasThurgood MarshallSouthern United Stateswhite peopleDeep Southmassive resistanceHarry F. ByrdCooper v. Aaronrace relationsUnited States Supreme CourtstatesHoward Universitygraduate schoolSweatt v. PainterMcLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regentsplaintiffsracial separationUNESCOThe Race Questionattempts at scientifically justifying racismGunnar MyrdalSoviet UnionCold WarDwight D. EisenhowerAmerican Bar AssociationUnited States District Court for the District of KansasMcKinley BurnettLucinda ToddSanta Fe RailroadLinda Carol BrownMonroe ElementarySumner ElementaryZelma HendersonWalter HuxmanBriggs v. ElliottSouth CarolinaDavis v. County School Board of Prince Edward CountyVirginiaGebhart v. BeltonDelawareBolling v. SharpeWashington, D.C.Barbara Rose JohnsMoton High SchoolDelaware Supreme CourtWalter ReutherUnited Auto WorkersUniversity of KansasJustice Departmentamicus curiaeforeign-policyTruman administrationJames P. McGranerySecretary of StateDean AchesonAnthony LesterHarold Hitz BurtonFred M. Vinsoncultural assimilationstates' rightsjudicial activismMendez v. WestminsterWhite Housejudicial restraintrecess appointmentSouthernchief justiceKenneth and Mamie Clarkpreferred white dolls over black dollsBrown IIBlack MondayPearl HarborRobert G. McCloskeyJohn Ben ShepperdArkansasOrval FaubusArkansas Army National GuardLittle Rock NineLittle Rock Central High SchoolU.S. Army101st Airborne DivisionFort CampbellInterpositionFlorida GovernorLeRoy CollinsMississippiMedgar EversJackson, Mississippi