Brazilian battleship São Paulo

Soon after, it was involved in the Revolt of the Lash (Revolta de Chibata), in which crews on four Brazilian warships mutinied over poor pay and harsh punishments for even minor offenses.The tow lines broke during a strong gale on 6 November, when the ships were 150 nmi (280 km; 170 mi) north of the Azores, and São Paulo was lost.Beginning in the late 1880s, Brazil's navy fell into obsolescence, a situation exacerbated by an 1889 coup d'état, which deposed Emperor Dom Pedro II, and an 1893 civil war.[11] The government of Brazil used some of the extra money from this economic growth to finance a naval building program in 1904,[2] which authorized the construction of a large number of warships, including three battleships.[2][4][18] The news shocked Brazil's neighbors, especially Argentina, whose Minister of Foreign Affairs remarked that either Minas Geraes or São Paulo could destroy the entire Argentine and Chilean fleets.[2][22] Despite this, the United States actively attempted to court Brazil as an ally; caught up in the spirit, U.S. naval journals began using terms like "Pan Americanism" and "Hemispheric Cooperation".[2] São Paulo was christened by Régis de Oliveira, the wife of Brazil's minister to Great Britain, and launched at Barrow-in-Furness on 19 April 1909 with many South American diplomats and naval officers in attendance.[29] A rumor that the king was on board, circulated by newspapers and reported to the Brazilian legation in Paris,[30][31] led revolutionaries to attempt to search the ship, but they were denied permission.[25] Soon after São Paulo's arrival, a major rebellion known as the Revolt of the Lash, or Revolta da Chibata, broke out on four of the newest ships in the Brazilian Navy.They objected to low pay, long hours, inadequate training, and punishments including bolo (being struck on the hand with a ferrule) and the use of whips or lashes (chibata), which eventually became a symbol of the revolt.[36] Humiliated by the revolt, naval officers and the president of Brazil were staunchly opposed to amnesty, so they quickly began planning to assault the rebel ships.Later research and interviews indicate that Minas Geraes' guns were fully operational, and while São Paulo's could not be turned after salt water contaminated the hydraulic system, British engineers still on board the ship after the voyage from the United Kingdom were working on the problem.[25] The American battleship Nebraska, which was in the area after transporting the body of the late Uruguayan Minister to the United States to Montevideo,[41] rendered assistance in the form of temporary repairs after the ships put in at Bahia.[3][29] The mutineers then sailed out of Rio de Janeiro's harbor, where the forts at Santa Cruz and Copacabana engaged her, damaging São Paulo's fire control system and funnel.[24] The crewmen aboard São Paulo attempted to join revolutionaries in Rio Grande do Sul, but when they found that the rebel forces had moved inland, they set course for Montevideo, Uruguay.[42] As a result, while Minas Geraes was thoroughly refitted from 1931 to 1938 in the Rio de Janeiro Naval Yard,[29] São Paulo was employed as a coast-defense ship, a role in which it remained for the rest of its service life.[59] American B-17 Flying Fortress bombers and British planes were launched to scout the Atlantic for the missing ship;[57][60] it was reported, incorrectly, as found on 15 November.

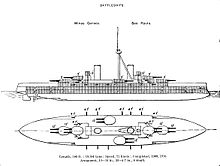

Brazilian aircraft carrier São Paulosea trialsSão PauloVickersBarrow-in-FurnessMinas Geraes-classbattleshipoverallnormalfull loadBabcock & Wilcox12-inch (304.8 mm) main guns3-pounder (47 mm)TurretsBarbettesdreadnoughtBrazilian NavyMinas Geraes classlaunchingcommissionedRevolt of the LashsisterMinas GeraesGrand FleetCopacabana Fort revoltMontevideoUruguayasylumRecifetraining vesselAzoresSouth American dreadnought raceMinas Geraes-class battleshipPedro II1893 civil warcoffeerubberJúlio César de NoronhaArmstrong Whitworththe namesake shipBahia classPará classnaval arms race among Brazil, Argentina, and Chile1902 treatylead shipMinister of Foreign Affairschristenedlaunchedfitting-outGreenockCherbourgBrazilian PresidentHermes Rodrigues da FonsecaLisbonManuel II5 October 1910 revolutionJoão Cândido FelisbertoAfro-BrazilianLei ÁureaDeodoroferruleamnestyRuy BarbosaFederal SenateChamber of DeputiesGuanabara BayRio Grande do SulhydraulicBrazil during World War IFirst World WarU-boatsRoyal NavyboilersNebraskaRaleighNew York Naval YardSperryBausch and Lombsuperfiringbulkheadcasemate3"/50 caliber gunsBethlehem Steel3 poundersGravesendBureau of StandardsGulf of GuacanayaboGuantánamo BayAlbert IElisabethTeresa CristinaTenente revoltsseized Fort CopacabanaRio de JaneiroLieutenantsecond lieutenantstorpedo boatSanta CruzCopacabanaVargas EraIbirapuera ParkConstitutionalist RevolutionflagshipblockadeRivadaviaMorenoGetúlio VargasRiver PlateBuenos AiresFlamengoFluminenseSecond World WarBadgerIron and Steel Corporation of Great Britainbreaking upEdoardo De MartinotroughB-17 Flying FortressBoard of TradeCustódio José de MelloFloriano PeixotoDesterroAquidabãNassauJosé Carlos de Carvalhocaptain