Benjamin Disraeli

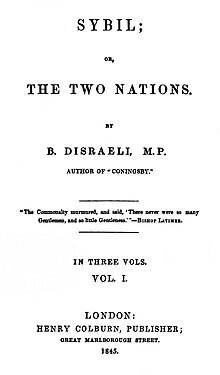

Disraeli is remembered for his influential voice in world affairs, his political battles with the Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, and his one-nation conservatism or "Tory democracy".Disraeli was born on 21 December 1804 at 6 King's Road, Bedford Row, Bloomsbury, London,[n 1] the second child and eldest son of Isaac D'Israeli, a literary critic and historian, and Maria (Miriam), née Basevi.[7][8][n 3] Historians differ on Disraeli's motives for rewriting his family history: Bernard Glassman argues that it was intended to give him status comparable to that of England's ruling elite;[10] Sarah Bradford believes "his dislike of the commonplace would not allow him to accept the facts of his birth as being as middle-class and undramatic as they really were".[22] It is not known whether Disraeli formed any ambition for a parliamentary career at the time of his baptism, but there is no doubt that he bitterly regretted his parents' decision not to send him to Winchester College,[23] one of the great public schools which consistently provided recruits to the political elite.[27] Although biographers including Robert Blake and Bradford comment that such a post was incompatible with Disraeli's romantic and ambitious nature, he reportedly gave his employers satisfactory service, and later professed to have learnt a good deal there.He enrolled as a student at Lincoln's Inn and joined the chambers of his uncle, Nathaniel Basevy, and then those of Benjamin Austen, who persuaded Isaac that Disraeli would never make a barrister and should be allowed to pursue a literary career.Disraeli impressed Murray with his energy and commitment to the project, but he failed in his key task of persuading the eminent writer John Gibson Lockhart to edit the paper."[45] He was still living with his parents in London, but in search of the "change of air" recommended by the family's doctors, Isaac took a succession of houses in the country and on the coast, before Disraeli sought wider horizons.Peel hoped that the repeal of the Corn Laws and the resultant influx of cheaper wheat into Britain would relieve the condition of the poor, and in particular the Great Famine caused by successive failure of potato crops in Ireland.Lord John Russell, the Whig leader who had succeeded Peel as prime minister, proposed in the Commons that the oath should be amended to permit Jews to enter Parliament.[152] There were Tory dissenters, most notably Lord Cranborne (as Robert Cecil was by then known) who resigned from the government and spoke against the bill, accusing Disraeli of "a political betrayal which has no parallel in our Parliamentary annals".[153] Even as Disraeli accepted Liberal amendments (although pointedly refusing those moved by Gladstone)[154] that further lowered the property qualification, Cranborne was unable to lead an effective rebellion.An initial attempt by Disraeli to negotiate with Archbishop Manning the establishment of a Catholic university in Dublin foundered in March when Gladstone moved resolutions to disestablish the Irish Church altogether.Urged by a clergyman to turn her thoughts to Jesus Christ in her final days, she said she could not: "You know Dizzy is my J.C."[172] In 1873, Gladstone brought forward legislation to establish a Catholic university in Dublin."[182] Under the stewardship of Richard Assheton Cross, the Home Secretary, Disraeli's new government enacted many reforms, including the Artisans' and Labourers' Dwellings Improvement Act 1875 (38 & 39 Vict.[193] On 14 November 1875, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, Frederick Greenwood, learnt from London banker Henry Oppenheim that the Khedive was seeking to sell his shares in the Suez Canal Company to a French firm.The following January, Sultan Abdülaziz agreed to reforms proposed by Hungarian statesman Julius Andrássy, but the rebels, suspecting they might win their freedom, continued their uprising, joined by militants in Serbia and Bulgaria.[236] British policy in South Africa was to encourage federation between the British-run Cape Colony and Natal, and the Boer republics, the Transvaal (annexed by Britain in 1877) and the Orange Free State.The governor of Cape Colony, Sir Bartle Frere, believing that the federation could not be accomplished until the native tribes acknowledged British rule, made demands on the Zulu and their king, Cetewayo, which they were certain to reject.The Earl, a friend of both Disraeli and Gladstone who would succeed the latter after his final term as prime minister, had journeyed to the United States to view politics there, and was convinced that aspects of American electioneering techniques could be translated to Britain.[259] Queen Victoria was prostrated with grief, and considered ennobling Ralph or Coningsby as a memorial to Disraeli (without children, his titles became extinct with his death), but decided against it on the ground that their means were too small for a peerage."[269] Disraeli's early "silver fork" novels Vivian Grey (1826) and The Young Duke (1831) featured romanticised depictions of aristocratic life (despite his ignorance of it) with character sketches of well-known public figures lightly disguised.[275] It draws on the events of his affair with Henrietta Sykes to tell the story of a debt-ridden young man torn between a mercenary loveless marriage and a passionate love at first sight for the eponymous heroine.[277] With Coningsby; or, The New Generation (1844), Disraeli, in Blake's view, "infused the novel genre with political sensibility, espousing the belief that England's future as a world power depended not on the complacent old guard, but on youthful, idealistic politicians.[287] In 2007 Parry wrote, "The tory democrat myth did not survive detailed scrutiny by professional historical writing of the 1960s [which] demonstrated that Disraeli had very little interest in a programme of social legislation and was very flexible in handling parliamentary reform in 1867.Blake argued that Disraeli's imperialism "decisively orientated the Conservative party for many years to come, and the tradition which he started was probably a bigger electoral asset in winning working-class support during the last quarter of the century than anything else"."[293] In Parry's view, Disraeli's foreign policy "can be seen as a gigantic castle in the air (as it was by Gladstone), or as an overdue attempt to force the British commercial classes to awaken to the realities of European politics."[295] Stanley Weintraub, in his biography of Disraeli, points out that his subject did much to advance Britain towards the 20th century, carrying one of the two great Reform Acts of the 19th despite the opposition of his Liberal rival, Gladstone.As an actor on the political stage he played many roles: Byronic hero, man of letters, social critic, parliamentary virtuoso, squire of Hughenden, royal companion, European statesman.He adds, "Before the 1990s...few biographers of Disraeli or historians of Victorian politics acknowledged the prominence of the antisemitism that accompanied his climb up the greasy pole or its role in shaping his own singular sense of Jewishness.

Disraeli (disambiguation)The Right HonourablePrime Minister of the United KingdomVictoriaWilliam Ewart GladstoneThe Earl of DerbyLeader of the OppositionMarquess of HartingtonThe Marquess of SalisburyChancellor of the ExchequerGeorge Ward HuntSir George Cornewall LewisSir Charles Wood, 3rd BaronetBloomsburyMayfairConservativeYoung EnglandMary Anne EvansIsaac D'IsraeliVivian GreyPopanillaThe Young DukeContarini FlemingIxion in HeavenThe Wondrous Tale of AlroyThe Rise of IskanderThe Infernal MarriageHenrietta TempleVenetiaConingsbyTancredLothairEndymionOne-nation conservatismClass collaborationConservatismModerate ConservatismMuscular LiberalismLiberal ConservatismEconomic LiberalismNoblesse obligePaternalismPragmaticSocial policyResponsibilityWelfare StateSubsidiarityEdmund BurkeLord Randolph ChurchillWinston ChurchillStanley BaldwinHarold MacmillanRab ButlerMichael HowardDavid CameronTheresa MayGeorge OsborneBoris JohnsonRishi SunakSybil, or The Two NationsConingsby, or The New GenerationIndustrial CharterConservative PartyTory Reform GroupBright BlueOne Nation Conservatives caucusmodern Conservative PartyLiberal PartyBritish Empireborn JewishMiddlesexsynagogueAnglicanHouse of CommonsRobert PeelCorn LawsLord DerbyLeader of the House of Commonsthat year's general election1874 general electionQueen VictoriaEarl of BeaconsfieldEastern questionOttoman EmpireSuez Canal CompanyRussian victories against the OttomansCongress of BerlinAfghanistanSouth Africaa massive speaking campaignthe 1880 general electionSephardic JewishAshkenazi JewishIberianVenetianIsaac CardosoGoldsmidsMocattasMontefioresSarah Bradfordday boydame schoolIslingtonRev John Potticary's schoolBlackheathBevis Marks SynagogueJudaismbaptisedChurch of EnglandBenjaminSharon TurnerConversionMembers of ParliamentJewishSampson GideonJews Relief Act 1858Winchester Collegepublic schoolsEliezer CoganHigham HillWalthamstowarticledsolicitorsCity of LondonRobert BlakePhilip Carteret Webb