Battle of the Trebia

The battle took place on the flood plain of the west bank of the lower Trebia River, not far from the settlement of Placentia (modern Piacenza), and resulted in a heavy defeat for the Romans.[4] This expansion gained Carthage silver mines, agricultural wealth, manpower, military facilities such as shipyards and territorial depth, which encouraged it to resist future Roman demands.[11] It was the long-standing Roman procedure to elect two men each year as senior magistrates, known as consuls, who in time of war would each lead an army.This marched north in May 218 BC, entering Gaul to the east of the Pyrenees, then taking an inland route to avoid Roman allies along the coast.[21] The Carthaginians crossed the Alps with 38,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry[16] in October, surmounting the difficulties of climate, terrain[16] and the guerrilla tactics of the native tribes.They also wanted to obtain allies among the north-Italian Gallic tribes from which they could recruit, to build up their army to a size which would enable it to effectively take on the Romans.The local tribe, the Taurini, were unwelcoming, so Hannibal promptly besieged their capital (near the site of modern Turin), stormed it, massacred the population and seized the supplies there.[note 1] Believing that he would therefore be facing a much larger Roman force than he had anticipated, Hannibal felt an even more pressing need to recruit strongly among the Cisalpine Gauls.[33] Next day each commander led out a strong force to personally reconnoitre the size and make-up of the opposing army, things of which they would have been almost completely ignorant.The next morning the Carthaginian cavalry bungled their pursuit and the Romans were able to set up camp on an area of high ground by the River Trebia at what is now Rivergaro, a little south west of Placentia.[48][49] Scipio waited for reinforcements while Hannibal camped at a distance on the plain on the other side of the river, gathering supplies and training the Gauls now flocking to his standard.As they were dispersed between a large number of settlements and many were burdened with plunder and looted food, the Carthaginians were easily routed and fled back to their camp.Hannibal was concerned that it would develop into a full-scale battle in a manner which he would not be able to control, so he recalled his troops and took personal command of reforming them immediately outside his camp.Sempronius was eager for a full-scale battle: he wished it to take place before Scipio fully recovered and so would be able to share the glory of an anticipated victory.He also preferred to fight a battle on the flat and open floodplain of the Trebia, where the manoeuvrability of his cavalry could be used to greatest effect, to the hillier ground away from the river where the Roman heavy infantry would have found it easier to dominate.[60][61] Most male Roman citizens were liable for military service and would serve as infantry, with a better-off minority providing a cavalry component.Approximately 1,200 of the infantry – poorer or younger men unable to afford the armour and equipment of a standard legionary – served as javelin-armed skirmishers known as velites; they each carried several javelins, which would be thrown from a distance, a short sword and a 90-centimetre (3 ft) circular shield.[39] Hannibal, however, had his younger brother Mago take 1,000 cavalry and 1,000 infantry during the night to the south of where he intended to fight the battle and secrete themselves in an old watercourse full of brush."[86] The confrontation broke down into a wheeling mass of cavalry, but with the Numidians refusing to withdraw, Sempronius promptly ordered out first his 6,000 velites and then his whole army; he was so eager to give battle that few, if any, of the Romans had eaten breakfast.The Numidians withdrew slowly and Sempronius pushed his whole army after them, in three columns, each 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) long, through the icy waters of the Trebia, which was running chest-high.Goldsworthy describes the fight put up by the Roman cavalry as "feeble",[91] while the military historian Philip Sabin says that the two contests were "speedily decided".[92] At the same time, unnoticed in the heat of battle, Mago's force of 2,000 had been making its way down the watercourse, onto the plain and into a position where they could attack the Romans' left rear.While all this was happening, the fighting between the two heavy infantry contingents had continued fiercely, with the more numerous and better armoured Romans getting the better of it; despite being weakened by many of their component units having to turn to the flank or rear.Sempronius, who was fighting with the Roman infantry, ordered them away from the site of the battle and, maintaining their formation, 10,000 of them re-crossed the Trebia and reached the nearby Roman-held settlement of Placentia without interference from the Carthaginians.[97] Goldsworthy states that the Romans "suffered heavily", but that "numbers of soldiers" straggled into Placentia or one of their camps in addition to the formed group of 10,000,[98] while John Lazenby argues that outside of the 12,500, "few" infantry escaped, although "most" of the cavalry did,[99] as does Leonard Cottrell.The consuls-elect recruited further legions, both Roman and from Rome's Latin allies; reinforced Sardinia and Sicily against the possibility of Carthaginian raids or invasion; placed garrisons at Tarentum and other places for similar reasons; built a fleet of 60 quinqueremes (large galleys); and established supply depots at Ariminum and Arretium (modern Arezzo) in Etruria in preparation for marching north later in the year.One was stationed at Arretium and one on the Adriatic coast; they would be able to block Hannibal's possible advance into central Italy and be well positioned to move north to operate in Cisalpine Gaul.[105] According to Polybius, the Carthaginians were now recognised as the dominant force in Cisalpine Gaul and most of the Gallic tribes sent plentiful supplies and recruits to Hannibal's camp.[109] Hannibal attempted without success to draw the main Roman army under Gaius Flaminius into a pitched battle by devastating the area.[116] The historian Toni Ñaco del Hoyo describes the Trebia, Lake Trasimene and Cannae as the three "great military calamities" suffered by the Romans in the first three years of the war.

The approximate extent of territory controlled by Rome and Carthage immediately before the start of the Second Punic War.

Hannibal's route from Iberia to Italy

Roman statuette of a

war elephant

recovered from

Herculaneum

A Carthaginian cavalryman of Hannibal's army, as depicted in 1891

Hannibal

The bowl of a

Montefortino-type helmet

, which was used by Roman infantry between c. 300 BC and 100 AD. The cheek guards are missing.

Modern interpretation of a slinger from the

Balearic Islands

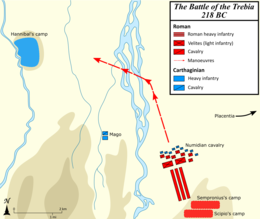

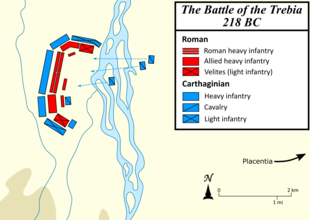

The Numidian cavalry provoke the Romans into leaving their camp.

The two armies form up and move towards contact.

The Carthaginians envelop the Roman army.

An Iberian warrior from bas-relief

c.

200 BC

. He is armed with a

falcata

and an oval shield.

Battle of Trebbia (1799)Second Punic WarMatthäus Merian the ElderTrebia RiverCarthageSempronius LongusHannibalSaguntumCrossing of the AlpsTicinusMutinaPlacentiaVictumulaeLake TrasimeneAger FalernusGeroniumCannaeSilva Litana1st Nola2nd Nola1st Beneventum3rd Nola1st Tarentum2nd Beneventum1st CapuaSilarus1st Herdonia2nd CapuaSapriportis2nd HerdoniaNumistroCanusium2nd Tarentum2nd PeteliaGrumentumMetaurusCrotonaInsubriaEbro RiverUpper Baetis1st New CarthageBaecula1st Carteia2nd CarteiaLilybaeumDecimomannuSyracuse1st Utica2nd UticaGreat PlainsPunic WarsMercenarySecondTrebbiaCarthaginiancavalryPiacenzaIberiaacross the AlpsCisalpine GaulPublius Scipiolight infantryBattle of TicinusSicilyNumidian cavalryroutedoutflankedcapturedGallicBattle of Lake TrasimeneBattle of CannaeFirst Punic WarBarcid conquest of HispaniaSiege of SaguntumMediterraneanNorth AfricaHamilcar BarcaCarthaginian Iberiahe greatly expandedBarcidsshipyardsHasdrubalEbro Treatysphere of influencebesieged, captured and sacked Saguntumdeclare warmagistratesconsulsGnaeusRoman colonistsCremonaRoman SenateHannibal's crossing of the Alpswar elephantHerculaneumCartagenaPyreneesHasdrubal BarcaMarseilleRiver RhoneAllobrogesBattle of Rhone Crossingguerrilla tacticswar elephantsPiedmontTaurinivalley of the Popontoon bridgeRiver Ticinusencampreconnoitrevelitesjavelinclose-orderlarge mêlée ensuedPublius Cornelius ScipiorearguardRiver PoRiver TrebiaRivergaroRiminiBrindisiClastidiumCasteggioformal battlesenveloped