Battle of Rorke's Drift

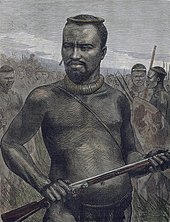

It was located near a drift, or ford, on the Buffalo (Mzinyathi) River, which at the time formed the border between the British colony of Natal and the Zulu Kingdom.On 20 January, after reconnaissance patrolling and building of a track for its wagons, Chelmsford's column marched to Isandlwana, approximately 10 km (6 mi) to the east, leaving behind the small garrison.[12] Captain Thomas Rainforth's G Company of the 1st/24th Foot was ordered to move up from its station at Helpmekaar, 16 kilometres (10 mi) to the southeast, after its own relief arrived, to further reinforce the position.2 Column under Brevet Colonel Anthony Durnford, late of the Royal Engineers, arrived at the drift and camped on the Zulu bank, where it remained through the next day.Chard rode ahead of his detachment to Isandlwana on the morning of 22 January to clarify his orders, but was sent back to Rorke's Drift with only his wagon and its driver to construct defensive positions for the expected reinforcement company, passing Durnford's column en route in the opposite direction.Soon thereafter, two survivors from Isandlwana – Lieutenant Gert Adendorff of the 1st/3rd NNC and a trooper from the Natal Carbineers – arrived bearing the news of the defeat and that a part of the Zulu impi was approaching the station.Upon hearing this news, Chard, Bromhead, and another of the station's officers, Acting Assistant Commissary James Dalton (of the Commissariat and Transport Department), held a quick meeting to decide the best course of action – whether to attempt a retreat to Helpmekaar or to defend their current position.Dalton pointed out that a small column, travelling in open country and burdened with carts full of hospital patients, would be easily overtaken and defeated by a numerically superior Zulu force, and so it was soon agreed that the only acceptable course was to remain and fight.With the garrison's 400-odd men[15] working diligently a defensive perimeter was quickly constructed out of mealie bags, biscuit boxes and crates of tinned meat.At about 3:30 p.m., a mixed troop of about 100 Natal Native Horse (NNH) under Lieutenant Alfred Henderson arrived at the station after having retreated in good order from Isandlwana.Prince Dabulamanzi was considered rash and aggressive, and this characterisation was borne out by his violation of King Cetshwayo's order to act only in defence of Zululand against the invading British soldiers and not carry the war over the border into enemy territory.At about 4:00 p.m., Surgeon James Reynolds, Otto Witt – the Swedish missionary who ran the mission at Rorke's Drift – and army chaplain Reverend George Smith came down from the Oscarberg hillside with the news that a body of Zulus was fording the river to the southeast and was "no more than five minutes away".At about 4:20 p.m., the battle began with Lieutenant Henderson's NNH troopers, stationed behind the Oscarberg, briefly engaging the vanguard of the main Zulu force.Upon witnessing the withdrawal of Henderson's NNH troop, Captain Stevenson's NNC company abandoned the cattle kraal and fled, greatly reducing the strength of the defending garrison.The hospital was becoming untenable; the loopholes had become a liability, as rifles poking out were grabbed at by the Zulus (who were still shot) yet if the holes were left empty, the Zulu warriors stuck their own weapons through in order to fire into the rooms.[34] Among the hospital patients who escaped were a Corporal Mayer of the NNC; Bombardier Lewis of the Royal Artillery, and Trooper Green of the Natal Mounted Police, who was wounded in the thigh by a bullet.The cattle kraal came under renewed assault and was evacuated by 10:00 p.m., leaving the remaining men in a small bastion around the storehouse: the British troops had withdrawn to the centre of the station, where a final defence had been hastily built.[43] Samuel Pitt, who served as a private in B Company during the battle, told The Western Mail in 1914 that the official enemy death toll was too low: "We reckon we had accounted for 875, but the books will tell you 400 or 500".[44][45][46] Lieutenant Horace Smith-Dorrien, a member of Chelmsford's staff, wrote that the day after the battle an improvised gallows was used "for hanging Zulus who were supposed to have behaved treacherously.Victor Davis Hanson responded to it directly in Carnage and Culture (also published as Why the West Has Won), saying, "Modern critics suggest such lavishness in commendation was designed to assuage the disaster at Isandhlwana and to reassure a skeptical Victorian public that the fighting ability of the British soldier remained unquestioned.Maybe, maybe not, but in the long annals of military history, it is difficult to find anything quite like Rorke's Drift, where a beleaguered force, outnumbered 40 to one, survived and killed 20 men for every defender lost".Depleted by injuries and fielding only ten men for much of the second half, the English outclassed and outfought the Australians in what quickly became known as the "Rorke's Drift Test".[59] While most of the men of the 1st Battalion, 24th Regiment of Foot (1/24) were recruited from the industrial towns and agricultural classes of England, principally from Birmingham and adjacent southwest counties, only 10 soldiers of the 1/24 that fought in the battle were Welsh.

Anglo-Zulu WarAlphonse de NeuvilleBritishUnited KingdomZulu KingdomJohn ChardGonville BromheadDabulamanzi kaMpandeBritish ArmySihayo's KraalZungwini MountainInyezaneIsandlwanaEshoweIntombeHlobaneKambulaGingindlovuZungeni MountainUlundimission stationRoyal Engineers24th Regiment of FootBattle of IsandlwanaVictoria CrossesZulu languageChurch of Swedentrading postJames RorkeBuffaloLord Chelmsford24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of FootBrevet Major104th FootNatal Native ContingentgarrisonAnthony DurnfordpontoonsGert AdendorffNatal CarbineersJames DaltonCommissariat and Transport DepartmentmealieloopholesOscarbergline of communicationassegainguni shieldMartini-HenrysCetshwayo kaMpandeSurgeon James ReynoldsmissionaryReverend George SmithcarbinePrivate Frederick HitchThe Defence of Rorke's DriftLady ButlerMartini–HenryassegaisWilliam Wilson AllenJohn WilliamsAlfred Henry HookRobert JonesWilliam JonesrevolversJames Henry ReynoldsNatal Mounted Policetheir own dead at IsandlwanaLabandThe Western MailHorace Smith-DorrienList of Zulu War Victoria Cross recipientsBattle of InkermanSecond Relief of LucknowDistinguished Conduct MedalsHenry Bartle FrereGarnet WolseleyVictor Davis HansonAlan Richard HillJohn Rouse Merriott Chard24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of FootFrederick HitchArmy Medical DepartmentJames Langley DaltonChristian Ferdinand Schiessmentioned in despatcheslieutenant-colonelFrank BourneRoyal Horse ArtilleryFrank Edward BourneArmy Service CorpsArmy Hospital CorpsC. H. M. KerrElizabeth ButlerH. Rider HaggardAndrew LangNorthern UnionAustraliathe Ashestest matchRorke's Drift TestRichard TuckerStanley BakerSouth Wales BorderersBirminghampower metalSabatonThe Last StandNorthern RhodesianJohn EdmondMilitary history of South AfricaRorke's Drift Art and Craft CentreRorke's Drift (video game)Battle of ChakdaraSiege of MalakandGeorge SmithFerdinand SchiessKnightThe Royal MagazineThe GuardianThe London GazetteSunday Mail (Brisbane)Osprey PublishingManchester University PressMilitary HeritagePorter, Whitworth