Anglican doctrine

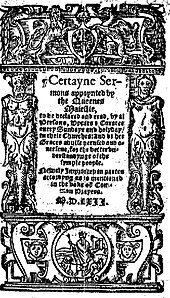

The second strand represents a range of Reformed Protestant teachings brought to England from neighbouring countries in the same period, notably Calvinism[Note 1] and Lutheranism.Nonetheless, metaphorical or spiritualised interpretations of some of the creedal declarations – for instance, the virgin birth of Jesus and his resurrection – have been commonplace in Anglicanism since the integration of biblical critical theory into theological discourse in the 19th century.[citation needed] The first four ecumenical councils of Nicea, Constantinople, Ephesus, and Chalcedon "have a special place in Anglican theology, secondary to the Scriptures themselves."[8] This authority is usually considered to pertain to questions of the nature of Christ (the hypostasis of divine and human) and the relationships between the Persons of the Holy Trinity, summarised chiefly in the creeds which emerged from those councils.The Thirty-Nine Articles list core Reformed doctrines such as the sufficiency of the Holy Scriptures for salvation, the execution of Jesus as "the perfect redemption, propitiation, and satisfaction for all the sins of the whole world", Predestination and Election.However, the real and essential presence of Christ in the eucharist is affirmed but "only after an heavenly and spiritual manner", consistent with a Reformed view of the Lord's Supper (cf.During the reigns of Edward VI and Elizabeth I, Thomas Cranmer and other English Reformers saw the need for local congregations to be taught Christian theology and practice.Some are straightforward exhortations to read scripture daily and lead a life of faith; others are rather lengthy scholarly treatises directed at academic audiences on theology, church history, the fall of the Christian Empire and the heresies of Rome.Primarily intended as a means of pursuing ecumenical dialogue with the Roman Catholic Church, the Quadrilateral soon became a "sine qua non" for essential Anglican identity.Given that the foundational elements of Anglican doctrine are either not binding or are subject to local interpretation, methodology has tended to assume a place of key importance.In this sense, Anglicans have viewed their theology as strongly incarnational – expressing the conviction that God is revealed in the physical and temporal things of everyday life and the attributes of specific times and places.This inherent sense of dynamism was articulated by John Henry Newman a century and a half ago, when he asked how, given the passage of time, we can be sure that the Christianity of today is the same religion as that envisioned and developed by Jesus Christ and the apostles.The reason this is the case is chiefly due to three factors: Newman's suggestion of two criteria for the sound development of doctrine has permeated Anglican thinking.The method by which this is accomplished is by the distillation of doctrine through, and its subordination to a dominant Anglican ethos consisting of the maintenance of order through consensus, comprehensiveness, and contract; and a preference for pragmatism over speculation.Anglican doctrinal methodology means concurrence with a base structure of shared identity: An agreement on the fundamentals of the faith articulated in the creeds; the existence of Protestant and catholic elements creating both a via media as well as a "union of opposites";[Note 4] and the conviction that there is development in understanding the truth, expressed more in practical terms rather than theoretical ones.A range of Presbyterian, Congregational, Baptist and other Puritan views gained currency in the Church in England, Ireland, and Wales through the late 16th and early 17th centuries.Although the Pilgrim Fathers felt compelled to leave for New England, other Puritans gained increasing ecclesiastical and political authority, while Royalists advocated Arminianism and the Divine Right of Kings.After the Restoration of 1660 and the 1662 Act of Uniformity reinforced Cranmer's Anglicanism, those wishing to hold to the stricter views set out at Westminster either emigrated or covertly founded non-conformist Presbyterian, Congregational, or Baptist churches at home.The schism with the Methodists in the 18th century had a theological aspect (with Methodism being Arminian), particularly concerning the Wesleyan emphasis on personal salvation by faith alone, although John Wesley continued to regard himself as a member of the Church of England.The High Churchmen gave birth to the Oxford Movement and the resulting Anglo-Catholic party of Anglicanism in the 19th century, which also saw the emergence of Liberal Christianity across the Protestant world.Beginning in the 17th century, Anglicanism came under the influence of latitudinarianism, chiefly represented by the Cambridge Platonists, who held that doctrinal orthodoxy was less important than applying rational rigour to the examination of theological propositions.The increasing influence of German higher criticism of the Bible throughout the 19th century, however, resulted in growing doctrinal disagreement over the interpretation and application of scripture.Figures such as Joseph Lightfoot and Brooke Foss Westcott helped mediate the transition from the theology of Hooker, Andrewes, and Taylor to accommodate these developments.In the early 20th century, the liberal Catholicism of Charles Gore and William Temple attempted to fuse the insights of modern biblical criticism with the theology expressed in the creeds and by the Apostolic Fathers, but the following generations of scholars, such as Gordon Selwyn and John Robinson questioned what had hitherto been the sacrosanct status of these verities.The consecration of bishops and the extension of sacraments to individuals based on gender or sexual orientation would ordinarily be matters of concern to the synods of the autonomous provinces of the Communion.

AnglicanismChristian theologyThirty-nine ArticlesBooks of HomiliesCaroline DivinesChicago–Lambeth QuadrilateralEpiscopal politySacramentsMinistryEucharistKing James VersionBook of Common PrayerLiturgical yearChurchmanshipCentralMonasticismSaintsJesus PrayerChristianityChristChristian ChurchFirst seven ecumenical councilsCeltic ChristianityAugustine of CanterburyMedieval cathedral architectureApostolic successionHenry VIIIEnglish ReformationThomas CranmerDissolution of the monasteriesChurch of EnglandEdward VIElizabeth IMatthew ParkerRichard HookerJames ICharles IWilliam LaudNonjuring schismLatitudinarianAnglo-CatholicismLiberalOxford MovementAnglican CommunionAnglican Communion historyArchbishop of CanterburyAnglican Communion Primates'MeetingsLambeth ConferenceBishopsAnglican Consultative CouncilEcumenismOrdination of womenWindsor ReportContinuing Anglican movementAnglican realignmentBartonville AgreementCongress of St. LouisNorth American Anglican ConferenceThe Books of Homiliesprima scripturaChurch fathersNiceneApostlesAthanasianscholasticismCharles SimeonReformedreligious ordersLutheranismCalvinismCatholiccatholicityPuritanismbroad churchlow churchhigh churchEvangelicalsAnglo CatholicsbetweenReformed AnglicanismArminian AnglicansBooks of Common PrayerordinalsThirty-Nine Articles of Religionlex orandi, lex credendiliturgyCranmerJohn PonetLancelot AndrewesJohn Jewelecumenical councilsApostles'Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateralcanon lawgeneral synodsbishopChristian movementsclergyLiberal ChristianityEvangelicalismMethodismschismsChristian doctrineProtestantRoman Catholic ChurchTrinityresurrection of Jesusoriginal sinexcommunicationContinental Reformedthree orders of ministryChurch of Swedenpresiding bishopUnited Episcopal Church of North AmericaNew TestamentsApocryphaCommon Worshipcritical theoryConstantinopleEphesusChalcedonhypostasisHoly TrinityReformertheology