A Preface to Paradise Lost

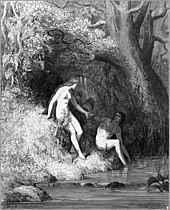

Eliot had said:There is a large class of persons, including some who appear in print as critics, who regard any censure upon a 'great' poet as a breach of the peace, as an act of wanton iconoclasm, or even hoodlumism.This technique is shown by when "Paradise is compared to the field of Enna", with the primary connection being how both locations are "one beautiful landscape to another (IV, 268)".[7] Lewis himself notes that sometimes, the logical underpinning of Milton's similes can stretch thin, as in the case of Satan's association with the unpleasant smell of fish.[3] Lewis "justly"[8] observes that this is done by making the sequence of Satan's entering Paradise resemble a dream:[8] as Satan approaches Paradise, Milton describes various tiers of the landscape, but just when it seems like we've reached the highest point, another layer or aspect is revealed, and "as in dream landscapes, we find that what seemed the top is not the top".[11] According to Matthew Jordan, Lewis is correct[6] in asserting that, in holding this position, Milton "belongs to the ancient orthodox tradition of European ethics",[3] but Lewis "downplays the significance of Milton using this tradition against kings rather than to bolster their position by affirming that society, and above all the king, embody such relations of natural superiority."In Paradise Lost we are to study what the poet, with his singing robes about him, has given," and not the "private theological whimsies"[13][3] that he "laid aside" during "his working hours as an epic poet":[3][4]Lewis's Milton hearkens back to the attempts of Bentley and Johnson to separate the private radical, heterodox, and "wild" man from the putatively orthodox achievement of the poem."Why," he writes, with a jibe at Saurat's emphasis on passion and sensuality, "must Noah always figure in our minds drunk and naked, never building the Ark?"Saurat, through his reading of the romantics, had brought not only the individual but the "unconscious" into Paradise Lost (184); Lewis, the figure of Anglican orthodoxy, for whom "Decorum" is the "grand masterpiece," prefers Milton the "very disciplined artist" to the admittedly "undisciplined man" of passion (90).[8] Lewis comments that, by his argument in book V, lines 856ff, Satan "renders himself ridiculous", since he "both loses in dignity and produces just the evidence to prove that he was not self-created".[3] Lewis rightly[12] rejects "the belief that Milton began by making Satan more glorious than he intended and then, too late, attempted to rectify the error", saying that "such an unerring picture of 'the sense of injured merit' in its actual operations upon character cannot have come about by blundering and accident."[3][12] Chapter 14, "Satan's Followers", discusses the infernal debate among the fallen angels in Hell in Book II of Paradise Lost.[3] It claims that the precise "name in English" for the sin committed by Eve is "Murder";[3] this analysis was criticized by Helen Gardner, although she agreed with Lewis's claim that the temptation and fall of Eve is not dramatically exploited, or lingered on:[12] as Lewis says, "the whole thing is so quick, each new element of folly, malice, and corruption enters so unobtrusively, so naturally, that it is hard to realize we have been watching the genesis of murder.Lewis's A Preface to Paradise Lost that the image of Milton as the great defender of a somehow Augustinian orthodoxy has taken hold."[12]Margaret Olofson Thickstun also sees Lewis's analysis as a response to Romantic attitudes, and sees support in it for the view that Satan may be redeemed (through apocatastasis):Surprisingly, support for reading apocastatic potential in Satan's story comes from another extremely orthodox reader of Paradise Lost: C. S. Lewis.

C.S. LewisEnglish languagePrefaceLiterary criticismOxford University PressEnglandC. S. LewisUniversity College of North Walesepic poemParadise LostJohn MiltonDenis SauratheresiesAugustinianHierarchicalRoman CatholicdedicationCharles WilliamsEpic PoetryT.S. Eliotinterpretsself-referential cyclethe epics of HomerBeowulfVirgilAeneidproper namessensory experiencesfield of Ennabeautifulthe resemblanceProserpinaDemeterGustave Dorékinesthetictheologypremodern literatureSt. Augustinethe ChurchorthodoxyHierarchyrepublicanismthe earthroyalismHeavencontradictionpoliticsCharles StuartEuropeansocietyhereticChristianProtestantPuritanpoetryseventeenth-centuryradical politicscriticismBentleyJohnsonheterodoxrevolutionary politicsantinomianworship of ManSauratthe romanticsunconsciousAnglicanmasterpieceartistegoismpersonifiedself-contradictionabsurdevidenceself-createdHelen GardnerMr. Williamsgeneralpoliticiansecret service agenta thing that peers in at bedroom or bathroom windowsPlatonicangelsincorporealmatterAdam and EveSexualitydisagreedThe FallEnglishStanley FishChristianityUnited StatesChristian traditionChristian faithAn Experiment in Criticismorthodoxillogical nonsenseRomanticShelleyHitlerapocatastasispersonal responsibilityontologicalFaded PageC. S. LewisBibliographySpirits in BondageReasonThe Pilgrim's RegressThe Screwtape LettersThe Great DivorceTill We Have FacesScrewtape Proposes a ToastLetters to MalcolmThe Space TrilogyOut of the Silent PlanetPerelandraThat Hideous StrengthThe Dark TowerThe Chroniclesof NarniaThe Lion, the Witch and the WardrobePrince CaspianThe Voyage of the Dawn TreaderThe Silver Chair