Óengus of Tallaght

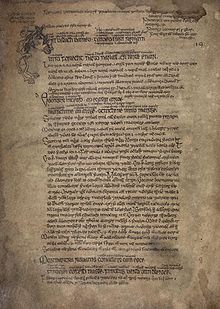

The most important sources include internal evidence from the Félire, a later Middle Irish preface to that work, a biographic poem beginning Aíbind suide sund amne ("Delightful to sit here thus") and the entry for his feast-day inserted into the Martyrology of Tallaght.Óengus's principal source was the Martyrology of Tallaght, an abbreviated version in prose of the Martyrologium Hieronymianum, but with a multitude of Irish saints added to their respective feast days.The usual method of determining a terminus post quem has been to argue from the careers of saints and kings referred to in the text, many of whom remain obscure.[6] The one thing that is usually accepted is that it was written no earlier than 797, when one of the rulers described in the prologue as having deceased, Donnchad mac Domnaill, king of Tara, died.[9] Dumville objects that this political argument glosses over the probability that while Bran and Donnchad gave way to overlords from rival dynasties, they were nevertheless succeeded by members of their family in their own tuatha or mórthuatha."[11] Third, having identified a number of saints in the Martyrology of Tallaght, the primary model for the Félire, he proposes obits extending to that of Teimnén or Temnán of Linn Duachaill, who died in 828.[12] In Dumville's view, the evidence is ambiguous, since the relationship of the extant copies of the Martyrology of Tallaght to the lost original which served as the source for the Félire is yet unclear.To similar effect, Óengus also holds up the example of Máel Ruain, who continues to offer support and comfort after his death, against that of the contemporary warrior-kings Donnchadh and Bran Ardchenn, whose strong exercise of power meant no such thing after theirs.[3] His earliest biographer in the ninth century[20] relates the wonderful austerities practised by Óengus in his "desert", and though he sought to be far from the haunts of men, his fame attracted a stream of visitors.

Saltair na RannRoman Catholic ChurchEastern Orthodox ChurchCuldeeMartyrology of TallaghtMiddle IrishDál nAraidiCounty Laois, IrelandMountrathFintan of ClonenaghclericOld IrishcommunityMáel RuainTallaghtSouth DublinLeinsterMartyrology of OengusmartyrologyLeabhar BreacMartyrologium HieronymianumJeromeEusebiusterminus post quemterminus ante quemDonnchad mac DomnaillBran Ardchenn mac MuiredaigFínsnechta mac CellaigCellach mac BrainConchobar mac DonnchadatuathaEmain MachaeArmaghClonmacnoiseT.M. Charles-EdwardsLindisfarneBangorDíserthermitangelsprayerruinedDísert ÓengusaCounty LimerickCounty Laoismonastery of TallaghtDublinlay brotherJohn ColganStokes, WhitleyBook of LeinsterÉigseCambridge Medieval Celtic StudiesColgan, JohnActa Sanctorum HiberniaeStudia Hibernicapublic domainCatholic EncyclopediaSaints of IrelandAbbánAbel of ReimsAdomnánAidan of LindisfarneAilbe of EmlyAileránAndrew the ScotAssicusAthrachtAutbodBaithéneBaldred of TyninghameBécánBenignus of ArmaghBerachBrandanBreageBrendanBrendan of BirrBrigit of KildareBroganBrónachBurianaGobhanMáedóc of FernsPatrickScuithinIrish poetryAislingDán DíreachMetrical DindshenchasIrish syllabic poetryKildare PoemsChief Ollam of IrelandIrish bardic poetryContention of the bardsIrish Literary RevivalWeaver PoetsAn GúmTáin Bó CúailngeMael Ísu Ua BrolcháinMuircheartach Ó CobhthaighGilla Mo Dutu Úa CaisideBaothghalach Mór Mac AodhagáinGiolla Brighde Mac Con MidheGofraidh Fionn Ó DálaighFlann mac LonáinDonnchadh Mór Ó DálaighLochlann Óg Ó DálaighFear Flatha Ó GnímhMathghamhain Ó hIfearnáinCormac Mac Con MidheEoghan Carrach Ó SiadhailFear Feasa Ó'n CháinteTadhg Olltach Ó an CháinteEochaidh Ó hÉoghusaProinsias Ó DoibhlinTarlach Rua Mac DónaillGilla Cómáin mac Gilla SamthaindeTadhg Dall Ó hÚigínnNiníne ÉcesColmán of CloyneCináed ua hArtacáinMuireadhach Albanach Ó DálaighCearbhall Óg Ó DálaighMáeleoin Bódur Ó MaolconaireDiarmaid Mac an Bhaird